Why this book matters

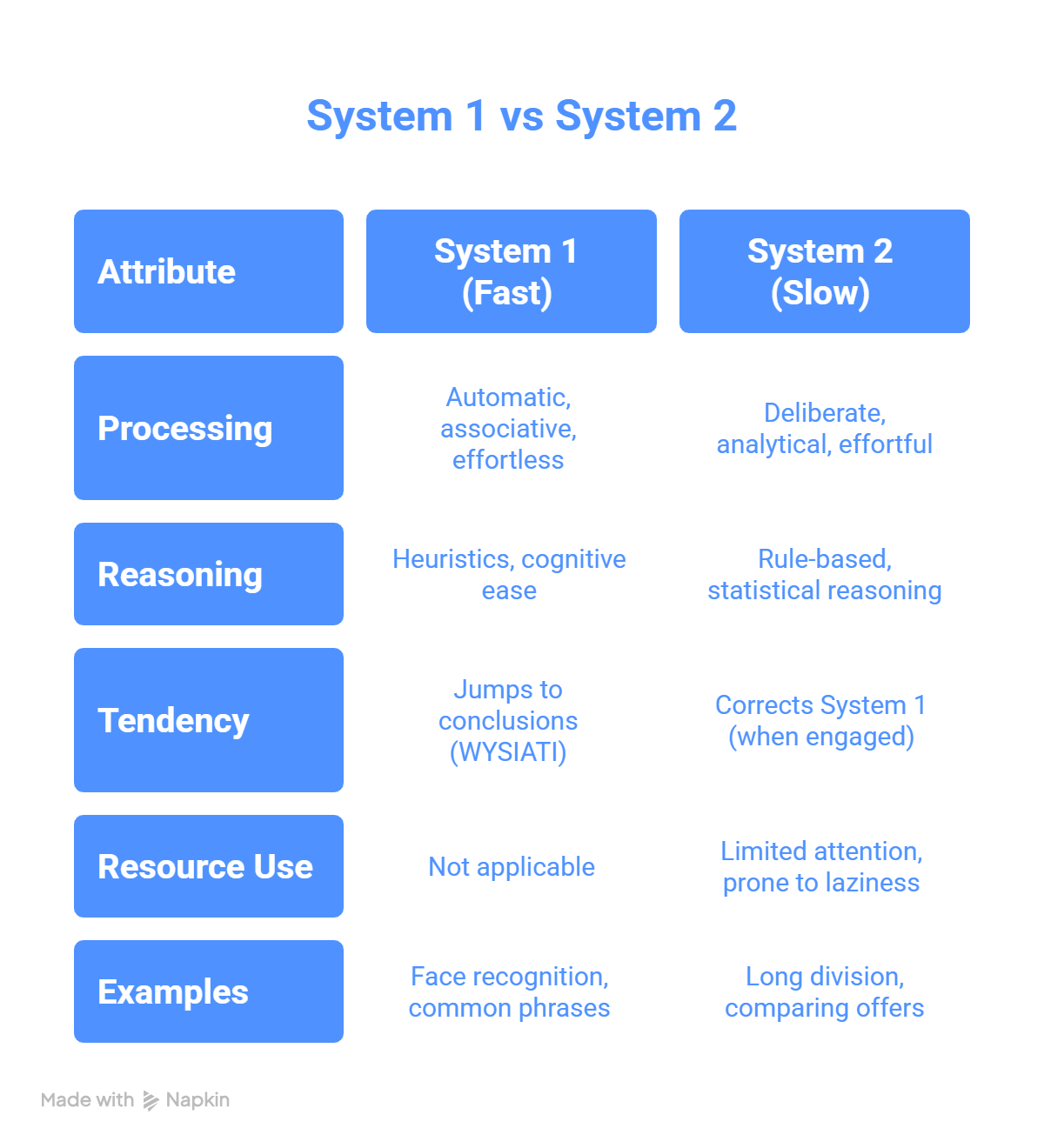

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow synthesizes decades of research on judgment and decision-making into a framework that explains why smart people make predictable mistakes. The book introduces two interacting modes of thought—System 1 (fast, automatic, associative) and System 2 (slow, effortful, rule-based)—and shows how heuristics (mental shortcuts) enable efficient cognition while also systematically biasing our judgments. It is foundational for fields from behavioral economics and public policy to product design and clinical practice. Kahneman’s explanations of loss aversion, framing, anchoring, base-rate neglect, the planning fallacy, and the peak–end rule have become common vocabulary for anyone who makes or studies decisions. Beyond cataloging biases, the book offers practical guardrails for better thinking: adopt simple policies, use checklists and algorithms where possible, design environments (choice architecture) that steer choices, and separate experienced from remembered well-being.

Chapter by chapter analysis

-

The Characters of the Story (Systems 1 & 2) – Introduces the dual-process model. System 1 runs on cognitive ease, pattern-matching, and quick associations; System 2 allocates attention and effort, but is lazy and endorses System 1’s impressions unless forced to intervene.

-

Attention, Effort, and Ego Depletion – Explains limited cognitive resources. Tasks that require sustained attention trigger pupil dilation and mental fatigue; when taxed, we default to the path of least resistance and accept superficial answers.

-

The Associative Machine & Cognitive Ease – Shows how priming, fluency, and mood produce illusory truth and confidence. When information is familiar, repeated, or smoothly processed, we judge it as truer and safer than it is.

-

WYSIATI: What You See Is All There Is – System 1 jumps to coherent stories from scant data. We overweight available evidence and ignore absent facts, leading to overconfidence and narrative fallacies.

-

Answering an Easier Question (Substitution) – When faced with a hard question (“How happy are you with your life?”), we unconsciously answer an easier one (“How happy am I right now?”), yielding systematic distortions.

-

The Law of Small Numbers – Humans overinterpret small samples and expect them to represent the population, producing spurious patterns and volatile conclusions.

-

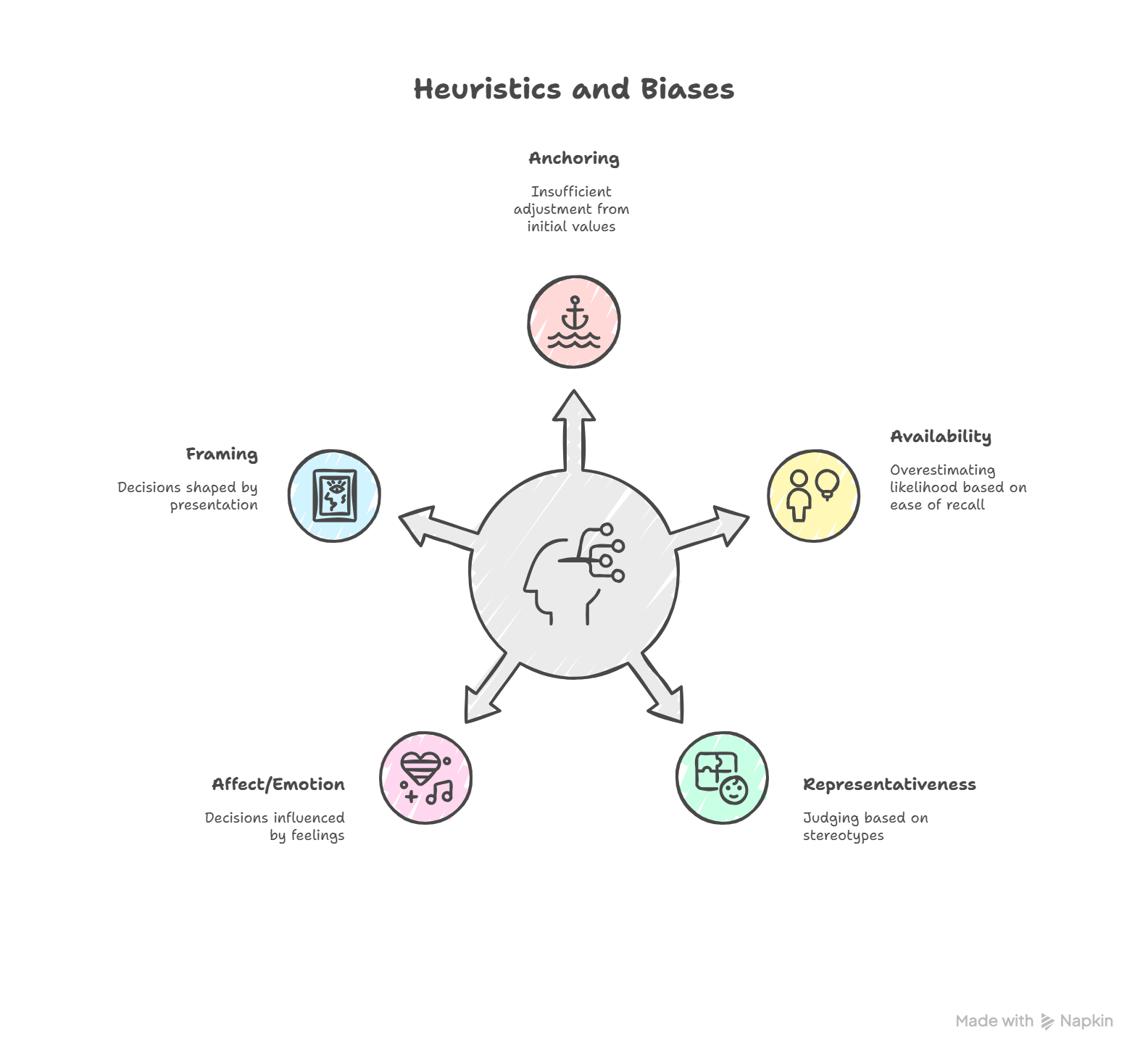

Anchoring – Arbitrary starting points (numbers, frames) drag estimates toward them. Even irrelevant anchors (a random wheel spin) sway judgments, via insufficient adjustment and priming of associative memory.

-

Availability & Salience – Likelihood is judged by ease of recall. Vivid events (plane crashes) seem more common than mundane risks (car accidents), skewing priorities in safety, media, and policy.

-

Representativeness, Stereotypes & Base-Rate Neglect – We match stories to prototypes and ignore base rates (prior probabilities). The classic “Tom W.” and “librarian/engineer” problems expose this bias.

-

Conjunction & Less-Is-More Effects – The conjunction fallacy (e.g., “Linda is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement”) reveals our appetite for plausible stories over logical probability.

-

Regression to the Mean – Extreme performances are usually followed by more ordinary ones; praise after good outcomes and punishment after bad often falsely get credit for natural regression.

-

Taming Intuitive Predictions – Replace gut forecasts with reference classes, base rates, and conservative adjustments. Formal models routinely outperform expert hunches in noisy domains.

-

Overconfidence: Illusions of Understanding & Validity – We weave causal stories from chance. Experts in low-feedback environments (stock-pickers) feel certain even when their accuracy is near random.

-

The Planning Fallacy & Inside vs. Outside View – Plans are built from optimistic scenarios; taking an outside view (statistics of similar projects) dramatically improves time and cost estimates.

-

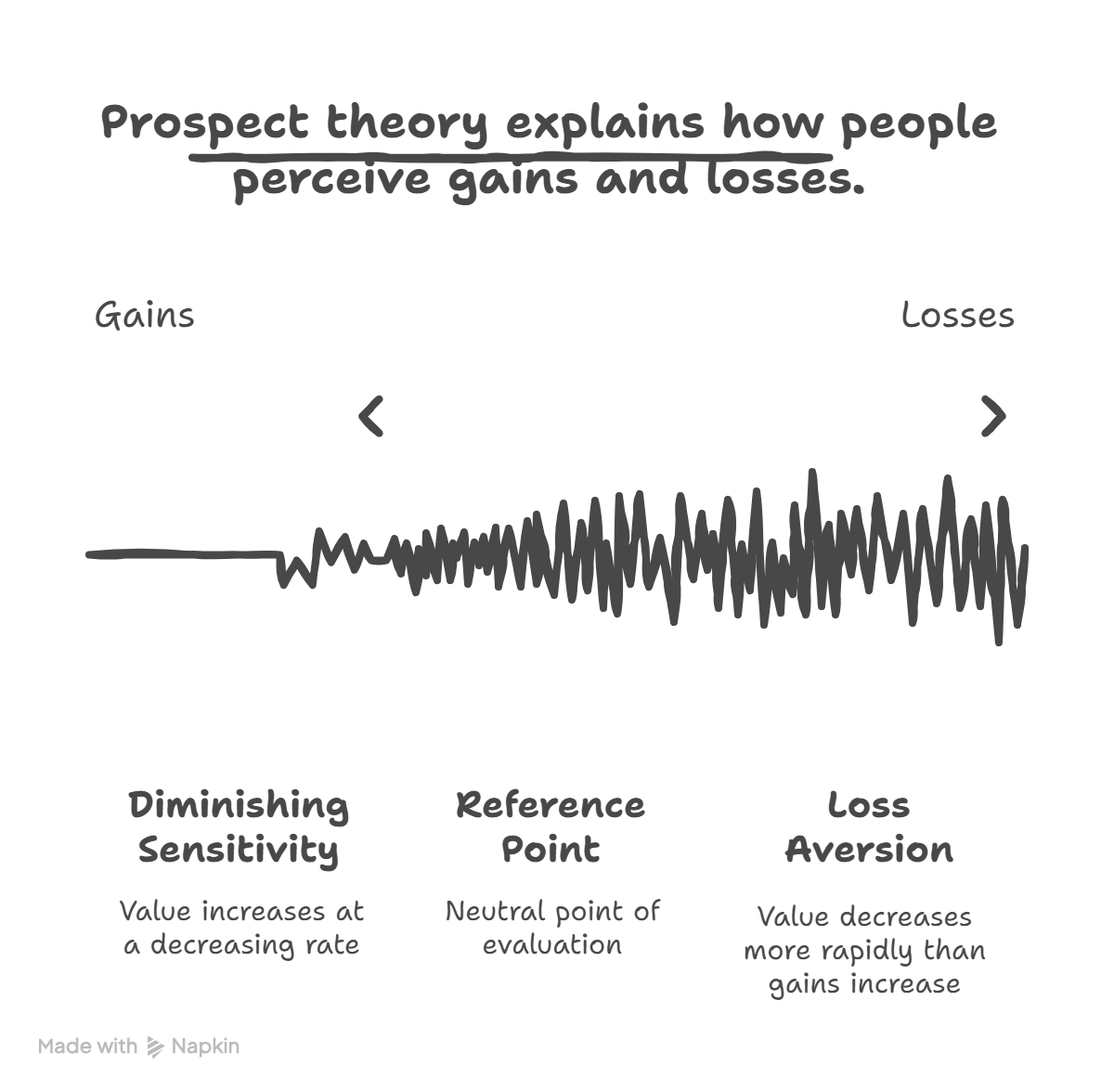

Prospect Theory – Describes how we evaluate gains and losses relative to a reference point with a value function that is concave for gains, convex for losses, and steeper for losses (loss aversion).

-

The Fourfold Pattern of Risk – Risk attitudes flip depending on probabilities and signs: risk-seeking for losses with high probability, risk-averse for gains, and the reverse for small probabilities—explaining lotteries and insurance.

-

Framing & Mental Accounting – Equivalent options feel different when framed (lives saved vs. lives lost). We keep separate mental ledgers, violating fungibility (e.g., treating a tax refund differently from salary).

-

Rare Events, Denominator Neglect & Risk Policies – Small probabilities distort choices via emotion and salience. Kahneman recommends policies (e.g., always buy or never buy travel insurance) to avoid one-off inconsistency.

-

Two Selves: Remembering vs. Experiencing – The remembering self summarizes episodes using the peak–end rule and duration neglect, while the experiencing self tracks moment-to-moment utility.

-

The Focusing Illusion & Well-Being – “Nothing in life is as important as you think when you are thinking about it.” We overestimate the impact of single factors (income, weather) on life satisfaction, guiding wiser policy and personal choices.

Main Arguments & Insights

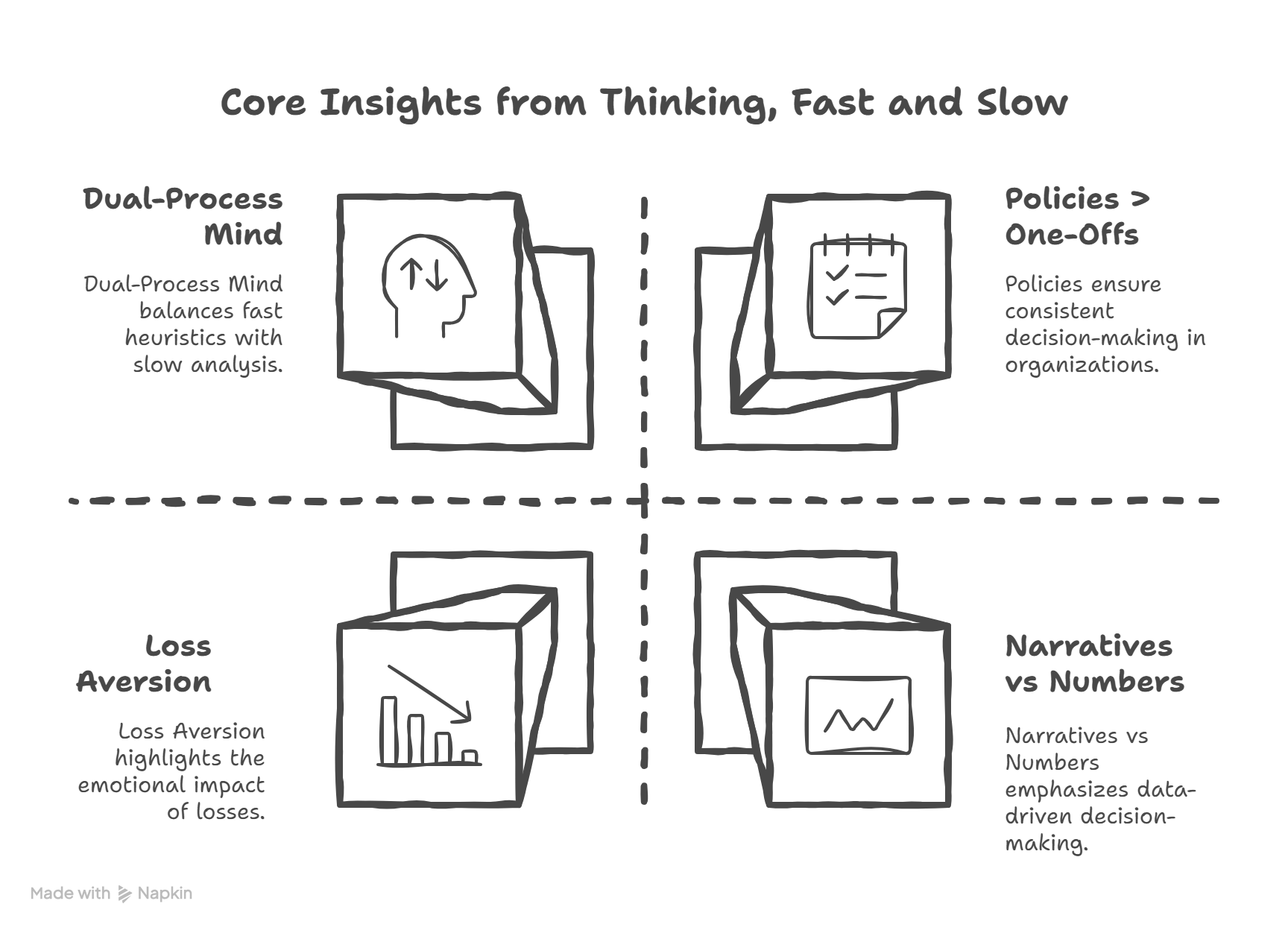

1. Dual-Process Cognition Governs Judgment: Human thinking is a tension between speed and accuracy. System 1’s heuristics are indispensable but biased; System 2 is corrective yet scarce and lazy. Good decision-making is about designing contexts where System 2 is triggered when it matters and about outsourcing judgment to rules and models in noisy domains.

2. Biases Are Predictable—and Manageable: Anchoring, availability, representativeness, and framing produce systematic errors, not random noise. The cure is structural: reference classes, checklists, premortems, statistical baselines, and default settings that make the best action the easiest action.

3. Loss Aversion Dominates Choices: Losses loom larger than gains, shaping markets, negotiations, and personal decisions. This explains the endowment effect, status quo bias, and puzzling patterns in risk-taking across domains.

4. Narratives Overwhelm Statistics: WYSIATI leads us to confident stories from incomplete data. Resist by privileging base rates and by separating signal from noise; when feasible, use algorithms over intuition.

5. Experience ≠ Memory: The peak–end rule and duration neglect mean our remembered utility can diverge from experienced utility. Designing experiences (medicine, CX, education) requires optimizing peaks and endings, not just duration or average intensity.

6. Policies Beat Case-by-Case Deliberation: One-off choices invite inconsistency. Risk policies (“always/never do X”) and choice architecture (smart defaults, precommitment) outperform ad-hoc reasoning under pressure.

Critical Reception & Perspectives

Upon its 2011 release, Thinking, Fast and Slow was widely acclaimed for unifying the heuristics-and-biases program into an accessible narrative and for its implications across economics, medicine, and law. It amplified the influence of behavioral economics after Kahneman’s 2002 Nobel Prize (for work culminating in prospect theory). The book became a long-running bestseller and a staple in MBA, public policy, and design curricula.

Critiques focus on several fronts. Dual-process oversimplification: Some cognitive scientists argue the System 1/System 2 split is a useful heuristic, not a literal neural dichotomy. Priming and replicability: A subset of social priming findings highlighted in the book faced replication failures, prompting healthy skepticism and calls for larger, pre-registered studies. Heuristics vs. ecological rationality: Gerd Gigerenzer and others contend that heuristics are often adaptive and efficient, not simply sources of bias—especially in environments where information is sparse and time is short. Despite debates, even critics concede the book’s enduring value: it maps the failure modes of human judgment and popularized countermeasures that practitioners can apply.

Real-World Examples & Implications

- Public Policy & Health: Opt-out defaults boost retirement savings and organ-donor rates. Framing vaccination benefits in terms of lives saved increases uptake. Premortems and checklists reduce diagnostic error and surgical complications.

- Product & UX Design: Avoid overload; use progress indicators and sensible defaults. Frame pricing and trials to mitigate loss aversion. Present base rates and risks with absolute frequencies (e.g., “1 in 1000”) to reduce denominator neglect.

- Investing & Risk Management: Counter overconfidence with rebalancing rules and investment policies. Prefer broad index funds to stock-picking in noisy markets. Use outside-view base rates for project and portfolio forecasts.

- Hiring & Performance: Structure interviews, score dimensions independently, and use formula-based aggregation to outdo intuition. Beware regression to the mean when interpreting extreme performance.

- Negotiation & Behavior Change: Reframe concessions to reduce perceived losses; chunk changes into gains and bundle losses. Use commitment devices and implementation intentions for follow-through.

- Law, Safety & Aviation: Standardize checklists, simulate rare events to counter availability and rarity neglect, and design no-blame reporting to combat hindsight bias and illusion of understanding.

Suggested Further Reading

- Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (Kahneman, Slovic, Tversky, 1982) – The foundational academic collection.

- Noise (Kahneman, Sibony, Sunstein, 2021) – How unwanted variability (noise) corrupts judgment and how to reduce it.

- Predictably Irrational (Dan Ariely, 2008) – Engaging experiments on systematic departures from rationality.

- Nudge (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) – Choice architecture for better decisions in health, wealth, and happiness.

- Superforecasting (Tetlock & Gardner, 2015) – Evidence-based techniques for more accurate probabilistic prediction.

- Thinking in Bets (Annie Duke, 2018) – Decision-making under uncertainty, separating process from outcomes.

- Risk Savvy (Gerd Gigerenzer, 2014) – A critique and complement: when heuristics are smart, and how to communicate risk.

- The Undoing Project (Michael Lewis, 2016) – Narrative history of the Kahneman–Tversky collaboration and its impact.