Why this book matters

Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money stands out because it reframes personal finance as a matter of behavior, not just knowledge. In a world obsessed with technical investing strategies and market predictions, Housel argues that how you think about money is often more important than what you know about it. The book’s core insight is that financial success is less about intelligence and more about self-awareness, patience, and emotional control. Housel draws on history, psychology, and real-life anecdotes to show that our relationship with money is deeply personal and often irrational—and that understanding our own biases is the key to making better decisions.

The book’s significance lies in its universal applicability—whether you’re a seasoned investor or just starting out, its lessons are relevant. Housel’s approachable style and focus on timeless principles make complex financial ideas accessible. The Psychology of Money has become a modern classic in personal finance, praised for its wisdom and humility. It’s not just a guide to getting rich—it’s a manual for thinking more clearly about money, happiness, and life.

Chapter by chapter analysis

-

No One’s Crazy – Housel opens by emphasizing that everyone’s financial decisions make sense to them, given their unique experiences. He illustrates how people’s attitudes toward money are shaped by the era and circumstances in which they grew up—someone raised during the Great Depression will see risk and savings differently than someone who only knew boom times. The chapter uses anecdotes and research to show that what seems irrational to one person may be perfectly logical to another, and that empathy is essential when considering others’ financial choices. This sets the stage for the book’s central theme: personal history shapes financial behavior.

-

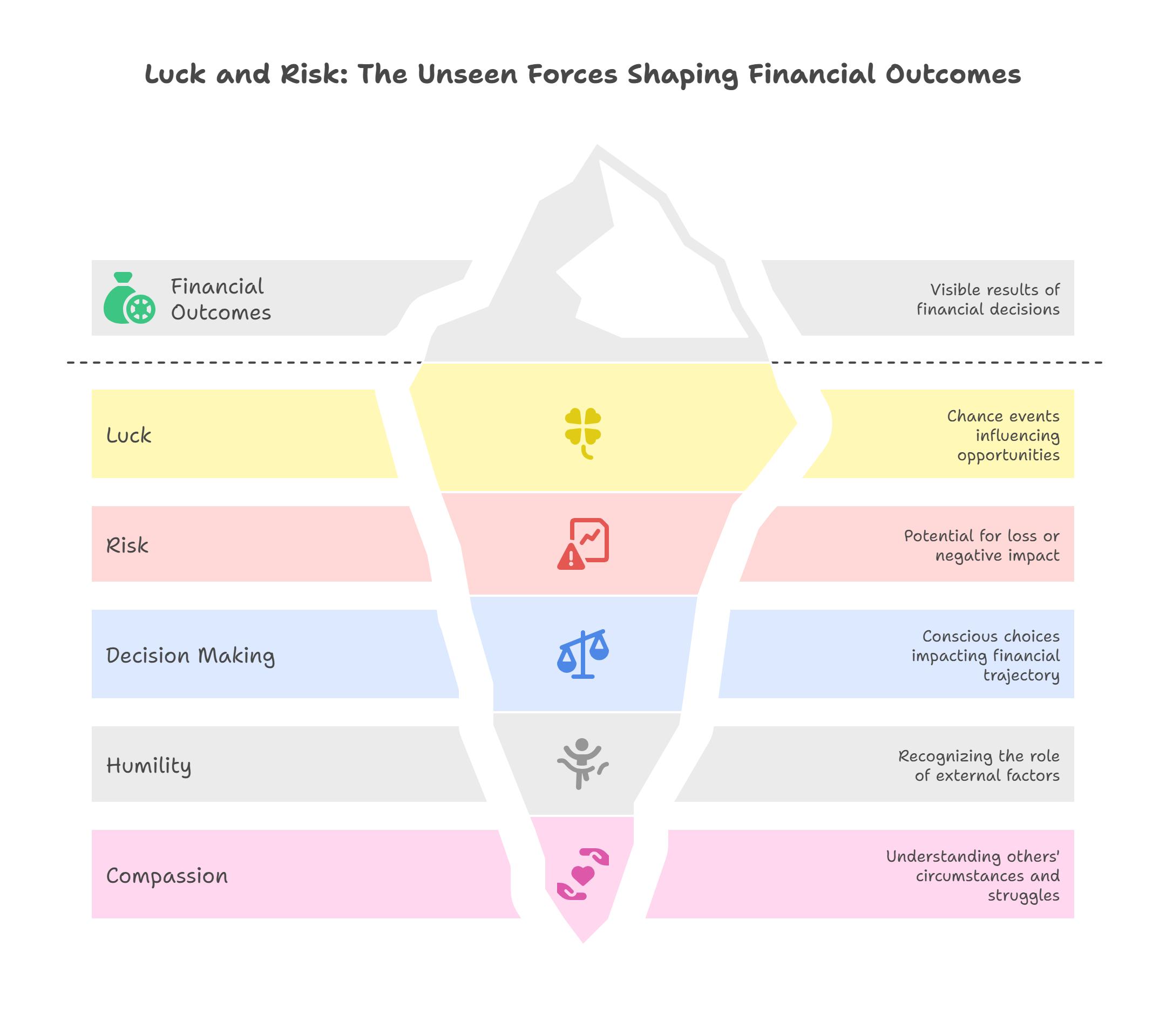

Luck & Risk – Housel explores the intertwined roles of luck and risk in financial outcomes. He contrasts the stories of Bill Gates (who attended one of the only high schools with a computer) and Kent Evans (a brilliant classmate who died young), showing how chance can be decisive. The lesson is to be humble about your successes and compassionate about others’ failures, recognizing that outcomes are often out of our control. Housel urges readers to focus on making good decisions rather than expecting perfect results, and to avoid judging others (or themselves) too harshly.

-

Never Enough – This chapter examines the dangers of insatiable desire. Housel uses the stories of Rajat Gupta and Bernie Madoff—both of whom lost everything by always wanting more—to illustrate that knowing when enough is enough is a rare and valuable skill. He contrasts their fates with Warren Buffett, who has maintained a sense of “enough” despite his vast wealth. The chapter warns that the pursuit of more can lead to ruin, and that contentment, not endless accumulation, is the real goal. Housel encourages readers to define their own sense of enough and to avoid moving the goalposts of satisfaction.

-

Confounding Compounding – Housel highlights the power of compounding, not just in finance but in life. He points out that small, consistent gains over time lead to extraordinary results, and that patience is a superpower in investing. Using Warren Buffett’s career as an example, Housel shows that the vast majority of Buffett’s wealth was accumulated after his 50th birthday, demonstrating that time and consistency matter more than outsized returns. The chapter also notes that compounding applies to relationships, knowledge, and reputation, not just money.

-

Getting Wealthy vs. Staying Wealthy – Housel distinguishes between the skills needed to build wealth (risk-taking, optimism) and those needed to keep it (frugality, paranoia). He stresses that survival is key—avoiding ruin is more important than chasing outsized gains. Getting rich often requires boldness and optimism, but staying rich requires humility, caution, and a healthy fear of losing what you have. The chapter encourages readers to focus on endurance and resilience, not just growth, and to always leave room for error.

-

Tails, You Win – This chapter discusses the outsized impact of rare, unpredictable events (“tail events”) in finance and life. Housel shows that a small number of big wins often account for most success—for example, a handful of investments drive the majority of returns in venture capital and stock markets. He encourages readers to accept that most things won’t work, but a few big successes can make all the difference. Embracing uncertainty and being open to tail events is essential for long-term success.

-

Freedom – Housel argues that the highest form of wealth is the ability to control your time. Money is valuable not for what it can buy, but for the autonomy it provides. He shares personal stories and research showing that people are happiest when they have control over their schedules and decisions. The chapter encourages readers to prioritize independence over luxury, suggesting that time freedom is the ultimate dividend of wealth.

-

Man in the Car Paradox – Housel explores the idea that people desire wealth to impress others, but in reality, others are rarely impressed. He calls this the “man in the car paradox”: when you see someone driving a fancy car, you admire the car, not the driver. The chapter suggests that true wealth is what you don’t see—the freedom and security, not the flashy displays. Housel warns against spending to signal status, as it rarely achieves the intended effect and can undermine financial security.

-

Wealth is What You Don’t See – This chapter reinforces the previous point: real wealth is hidden. Spending to display wealth often undermines the very thing people are trying to achieve. Housel explains that wealth is the money you don’t spend—the assets and options you retain. He encourages readers to focus on building invisible wealth rather than visible consumption, and to remember that restraint is a key ingredient of financial success.

-

Save Money – Housel emphasizes the importance of saving, regardless of income. He argues that building wealth is more about your savings rate than your investment returns. Saving gives you options, flexibility, and peace of mind, and it’s possible to build wealth even with modest earnings if you consistently save. The chapter dispels the myth that only high earners can become wealthy, highlighting the power of frugality and discipline, and the freedom that comes from living below your means.

-

Reasonable > Rational – Housel suggests that being “reasonable” with money—making choices you can stick with—is better than being perfectly rational. Personal finance is emotional, and systems that work for you are better than theoretical ideals. He argues that it’s more important to have a plan you can follow than to optimize for maximum returns, and that understanding your own psychology is key to long-term success. The chapter encourages readers to embrace strategies that are sustainable for them, even if they aren’t mathematically perfect.

-

Surprise! – Housel warns that the future is always uncertain. He discusses how history is full of surprises and that the biggest financial events are often those no one saw coming. The lesson is to expect the unexpected and to build plans that can withstand shocks. Housel encourages flexibility and resilience, rather than rigid plans, and to be wary of overconfidence in predictions.

-

Room for Error – This chapter advocates for margin of safety in all financial decisions. Housel recommends planning for the unexpected and avoiding overconfidence. He suggests keeping a buffer—extra savings, conservative assumptions, and backup plans—to protect against bad luck or mistakes. The chapter emphasizes that resilience is more important than precision, and that surviving setbacks is the key to long-term success.

-

You’ll Change – Housel reminds readers that their goals and desires will evolve over time. He shares stories of people whose ambitions shifted dramatically over the years, and encourages readers to avoid locking themselves into rigid paths. The chapter suggests building flexibility into financial plans to accommodate life’s changes, and to periodically reassess what you want from your money and your life.

-

Nothing’s Free – Housel argues that everything has a price, even if it’s not obvious. Volatility, uncertainty, and stress are the costs of long-term investing. He explains that there are no free lunches in finance, and that enduring discomfort is often the price of achieving good returns. The chapter encourages readers to accept these costs rather than trying to avoid them entirely, and to recognize that paying the price is part of the process.

-

You & Me – Housel explains that everyone’s financial goals and risk tolerances are different. He cautions against copying others’ strategies without considering your own situation. The chapter discusses how personal values, experiences, and circumstances shape what makes sense for each individual, and that comparing yourself to others is often counterproductive. Housel encourages readers to define success on their own terms.

-

The Seduction of Pessimism – Housel explores why pessimism sounds smarter than optimism, especially in finance. He examines the psychological reasons we are drawn to negative predictions and why bad news grabs our attention. The chapter encourages a balanced, long-term perspective, noting that progress is often slow and setbacks are inevitable, but optimism is justified over the long run.

-

When You’ll Believe Anything – Housel examines the stories we tell ourselves about money, and how narratives can lead us astray. He urges skepticism and self-reflection, warning that compelling stories can override facts and lead to poor decisions. The chapter discusses the dangers of confirmation bias and the importance of questioning your own assumptions, especially when making financial choices.

-

All Together Now – This chapter summarizes the book’s main lessons: save, be patient, respect luck and risk, and focus on what you can control. Housel ties together the previous chapters, emphasizing that financial success is about behavior, not brilliance, and that humility, patience, and adaptability are the most important traits. He encourages readers to focus on the basics and to avoid overcomplicating their approach to money.

-

Confessions – In the final chapter, Housel shares his own financial philosophy and admits his mistakes, reinforcing the book’s message of humility and lifelong learning. He reveals his personal approach to money—simple, conservative, and focused on independence—and encourages readers to find what works for them, rather than chasing perfection or imitation.

Main Arguments & Insights

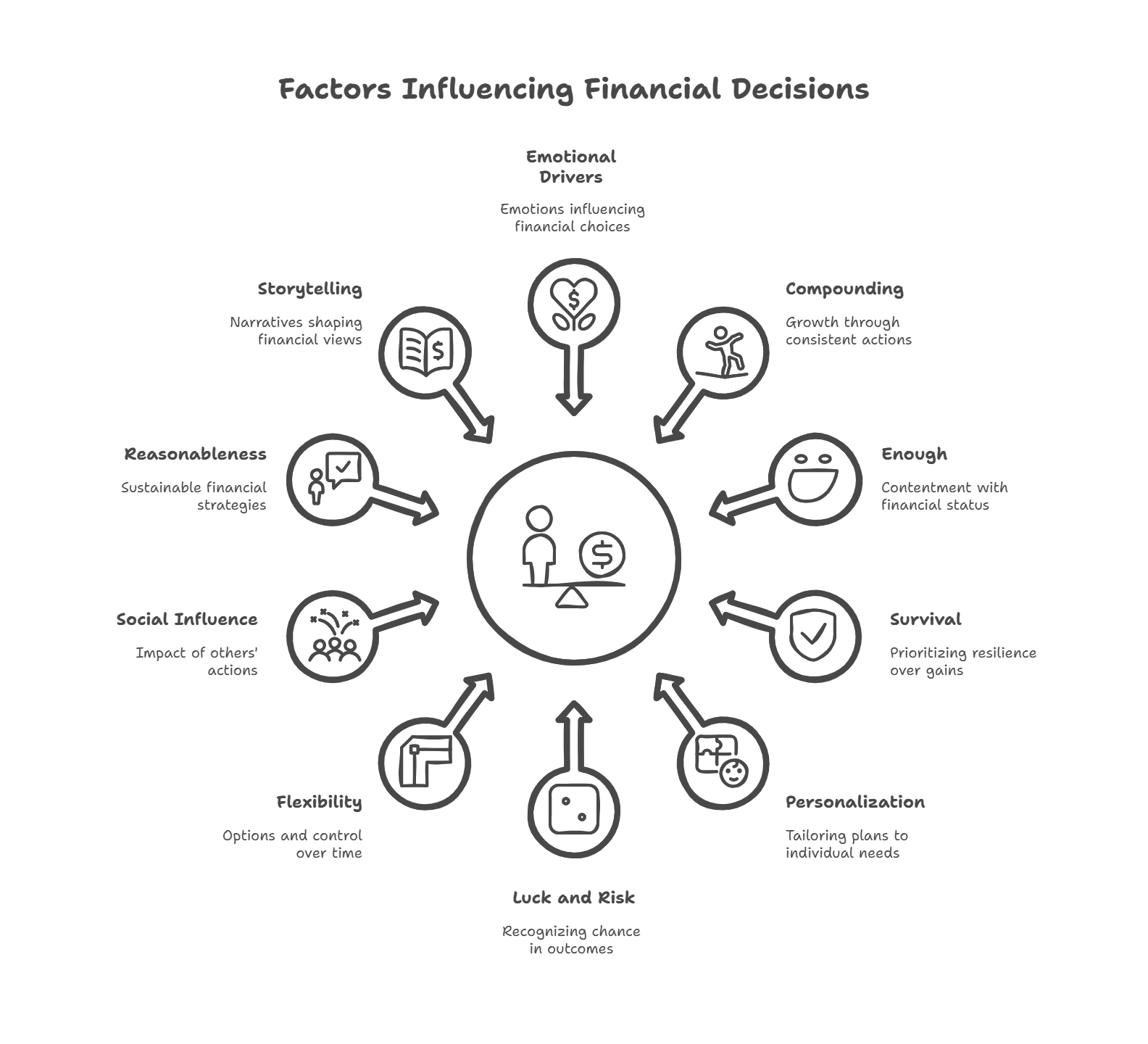

1. Money is Emotional, Not Logical: Housel’s central argument is that financial decisions are driven by emotion, not logic. Our upbringing, experiences, and even random chance shape how we think about risk, reward, and wealth. The book uses vivid stories to show that what seems irrational to one person may be perfectly logical to another, depending on their life context. Recognizing this helps us avoid judgment, fosters empathy, and leads to better choices. Housel’s insight is that understanding your own emotional triggers and biases is more important than mastering technical financial knowledge.

2. The Power of Compounding and Time: The book repeatedly stresses that small, consistent actions over time lead to extraordinary results. Whether it’s saving, investing, or learning, compounding is the most powerful force in finance—and it requires patience and discipline. Housel uses Warren Buffett’s career as a case study, showing that the vast majority of Buffett’s wealth was accumulated late in life, thanks to decades of compounding. The lesson is that time in the market, not timing the market, is what matters most, and that the benefits of compounding extend to relationships, reputation, and knowledge as well.

3. Enough is the Key to Happiness: Housel argues that knowing what is “enough” is more important than maximizing wealth. The endless pursuit of more can lead to ruin, while contentment brings peace and security. Through cautionary tales of people undone by greed, the book shows that defining your own sense of enough—and sticking to it—prevents lifestyle inflation and financial stress. This insight encourages readers to set boundaries, avoid comparison, and focus on what truly matters to them.

4. Survival and Resilience Trump Everything: Avoiding catastrophic mistakes is more important than chasing big wins. Housel’s advice: “You have to survive to succeed.” This means planning for uncertainty, leaving room for error, and prioritizing resilience over optimization. The book draws parallels to business and investing, where staying in the game is more important than maximizing every opportunity. Housel encourages readers to build buffers, expect surprises, and value endurance over brilliance.

5. Personal Finance is Personal: There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Housel emphasizes that your financial plan should fit your own goals, values, and temperament—not someone else’s. The book highlights how personal circumstances, risk tolerance, and life stage shape what makes sense for each individual. Housel’s insight is that copying others’ strategies without considering your own context can lead to disappointment or disaster. Instead, he urges readers to define success on their own terms and to be honest about what they want from money.

6. Luck, Risk, and Humility: The book explores the intertwined roles of luck and risk in financial outcomes. Housel shows that success is never entirely due to skill, nor is failure always due to mistakes. This perspective fosters humility, gratitude, and compassion for others. The lesson is to avoid arrogance in success, be gentle with yourself in failure, and recognize the limits of control in a complex world.

7. The Value of Flexibility and Optionality: Housel argues that saving money and building wealth are not just about consumption, but about buying flexibility and control over your time. The book shows that wealth is what you don’t see—the options and freedom it provides, not the visible displays of status. This insight reframes saving as a way to create choices and independence, rather than as deprivation.

8. The Dangers of Comparison and Social Influence: The book warns against the trap of comparing yourself to others, especially in a world of social media and conspicuous consumption. Housel explains that most people’s financial situations are invisible, and that chasing status or mimicking others’ lifestyles can lead to dissatisfaction and poor decisions. The insight is to focus on your own values and goals, and to resist the pressure to keep up with others.

9. The Importance of Reasonableness Over Rationality: Housel suggests that being “reasonable” with money—making choices you can stick with—is better than being perfectly rational. Personal finance is emotional, and systems that work for you are better than theoretical ideals. The book encourages readers to embrace strategies that are sustainable for them, even if they aren’t mathematically perfect, and to prioritize consistency over optimization.

10. The Role of Storytelling and Narrative: The book highlights how the stories we tell ourselves about money shape our decisions, for better or worse. Housel urges skepticism and self-reflection, warning that compelling narratives can override facts and lead to poor choices. The insight is to question your own assumptions, be aware of confirmation bias, and seek evidence over anecdotes.

Critical Reception & Perspectives

The Psychology of Money was published in 2020 and quickly became a bestseller, praised for its clarity, wisdom, and accessibility. On the positive side, reviewers and readers alike have lauded Housel’s storytelling and ability to distill complex ideas into memorable lessons. The book is frequently cited as a must-read for anyone interested in personal finance, and its influence has spread to business leaders, educators, and everyday readers. Many appreciate its focus on humility, patience, and the human side of money.

However, some critics have noted that the book’s advice can be broad or self-evident. A few reviewers argue that Housel’s anecdotes, while engaging, sometimes lack depth or actionable detail. Others point out that the book’s emphasis on behavior over technical knowledge may leave readers wanting more concrete strategies. Nonetheless, even skeptics generally agree that the book’s core messages—about humility, patience, and the unpredictability of life—are valuable reminders in a world obsessed with quick financial fixes.

In summary, The Psychology of Money is widely regarded as a modern classic in personal finance. Its blend of storytelling, psychology, and practical wisdom has resonated with millions, making it a staple recommendation for anyone seeking a healthier relationship with money.

Real-World Examples & Implications

Housel’s principles in The Psychology of Money have resonated widely, with real-world implications across personal, professional, and societal domains:

-

Personal Finance and Investing: Many readers have reported a shift in their approach to saving, spending, and investing after reading the book. The emphasis on patience, compounding, and defining “enough” has inspired people to set more realistic financial goals, automate savings, and avoid risky speculation. For example, some have adopted a “pay yourself first” approach, prioritized emergency funds, or chosen index funds over chasing hot stocks. The book’s message about the power of compounding has led to a renewed focus on starting early and letting time work in one’s favor.

-

Financial Advising and Education: Financial advisors and educators frequently use the book to teach clients and students about the behavioral side of money. Its lessons on humility, risk, and personal values have become part of the curriculum in many financial literacy programs. Advisors cite the book to help clients understand why sticking to a plan is more important than chasing market trends, and to encourage conversations about risk tolerance, life goals, and the emotional side of investing. Some schools and universities have incorporated the book into personal finance courses, using its stories to make abstract concepts relatable.

-

Business, Leadership, and Corporate Culture: Leaders in business have cited the book’s insights on risk, luck, and decision-making to shape company strategy and culture. The idea that “survival is success” has influenced risk management policies, with companies building more robust contingency plans and buffers. Some organizations have used the book to foster a culture of humility and long-term thinking, encouraging employees to focus on sustainable growth rather than short-term wins. The book’s lessons on the unpredictability of outcomes have also been used in leadership training to promote adaptability and resilience.

-

Wealth Management and Estate Planning: Wealth managers have used Housel’s ideas to help clients define what “enough” means for them and their families, leading to more thoughtful estate planning and charitable giving. The book’s focus on intergenerational differences in money attitudes has helped families navigate conversations about inheritance, legacy, and financial values.

-

Public Policy and Social Programs: Policymakers and nonprofit organizations have drawn on the book’s insights to design programs that account for behavioral biases in saving and spending. For example, automatic enrollment in retirement plans and “nudge” strategies in public policy reflect the book’s emphasis on making good financial behaviors easier and more likely. The recognition that financial decisions are emotional and context-dependent has influenced the design of social safety nets and financial education campaigns.

-

Media, Popular Culture, and Online Communities: The book’s maxims—such as “save money, not for the sake of saving, but for the flexibility it gives you”—have become widely quoted in financial media, podcasts, and online forums. Personal finance bloggers and influencers often reference Housel’s stories and principles when discussing topics like FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early), frugality, and the psychology of spending. The book’s ideas have sparked discussions about the dangers of comparison, the importance of defining personal success, and the value of financial independence.

-

Everyday Life and Relationships: Beyond finance, the book’s lessons about patience, humility, and self-awareness have broader implications. Readers have applied its principles to relationships—such as communicating openly about money with partners, setting shared goals, and respecting different attitudes toward risk. The book’s focus on the emotional side of money has helped people recognize and address financial anxiety, avoid lifestyle inflation, and make decisions that align with their values. Some have used the book’s insights to guide career choices, prioritize time over money, or pursue work-life balance.

-

Cultural Shift in Self-Improvement: The book has contributed to a broader cultural shift away from “get rich quick” schemes and toward a mindset of slow, steady improvement. Its popularity has encouraged more people to view financial well-being as a lifelong process, emphasizing habits, systems, and self-reflection over luck or intelligence. The idea that “personal finance is personal” has empowered individuals to craft their own paths, rather than blindly following trends or advice.

Suggested Further Reading

If The Psychology of Money sparked your interest, consider these related books:

-

Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez (2008) – A classic on transforming your relationship with money and achieving financial independence.

-

The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko (1996) – Explores the habits and behaviors of America’s wealthy, emphasizing frugality and discipline.

-

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman (2011) – A deep dive into the psychology of decision-making, including financial choices.

-

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki (1997) – A popular book on financial education and mindset.

-

The Simple Path to Wealth by JL Collins (2016) – A straightforward guide to investing and financial independence.

-

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics by Richard H. Thaler (2015) – Chronicles the rise of behavioral economics and its impact on finance.

-

Research articles on behavioral finance and decision-making: For a scientific perspective, explore work by Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and Richard Thaler on how psychology shapes economic choices.