Why this book matters

John Williams’ Stoner is frequently cited as “the greatest novel you have never read,” though in recent years it has shed its obscurity to become a beloved classic. On the surface, it is an unassuming story about an unassuming man: William Stoner, an assistant professor of English at the University of Missouri during the first half of the 20th century. He is not a war hero; he is not a famous scholar; his marriage is a disaster; and he is estranged from his only child. Yet, the book matters profoundly because it challenges our modern, loud definitions of success. It is a radical assertion that an “ordinary” life—filled with quiet disappointments, small victories, and a steadfast commitment to one’s craft—is a life worth living, and perhaps even a heroic one.

The core thesis of the novel, if one can extract a thesis from such a tender narrative, is the dignity of endurance and the sanctuary of the mind. Williams presents a protagonist who finds meaning not in external validation, but in the rigorous, private pursuit of truth and literature. In a world increasingly obsessed with personal branding and visible achievement, Stoner offers a meditative counter-argument: that integrity is an internal state, maintained often at great cost, and that the love of work can be a sufficient refuge against a hostile world. It is a masterclass in empathy, forcing the reader to look closely at the “gray” people in the background of history and recognize their complex, vibrant humanity.

Chapter by chapter analysis

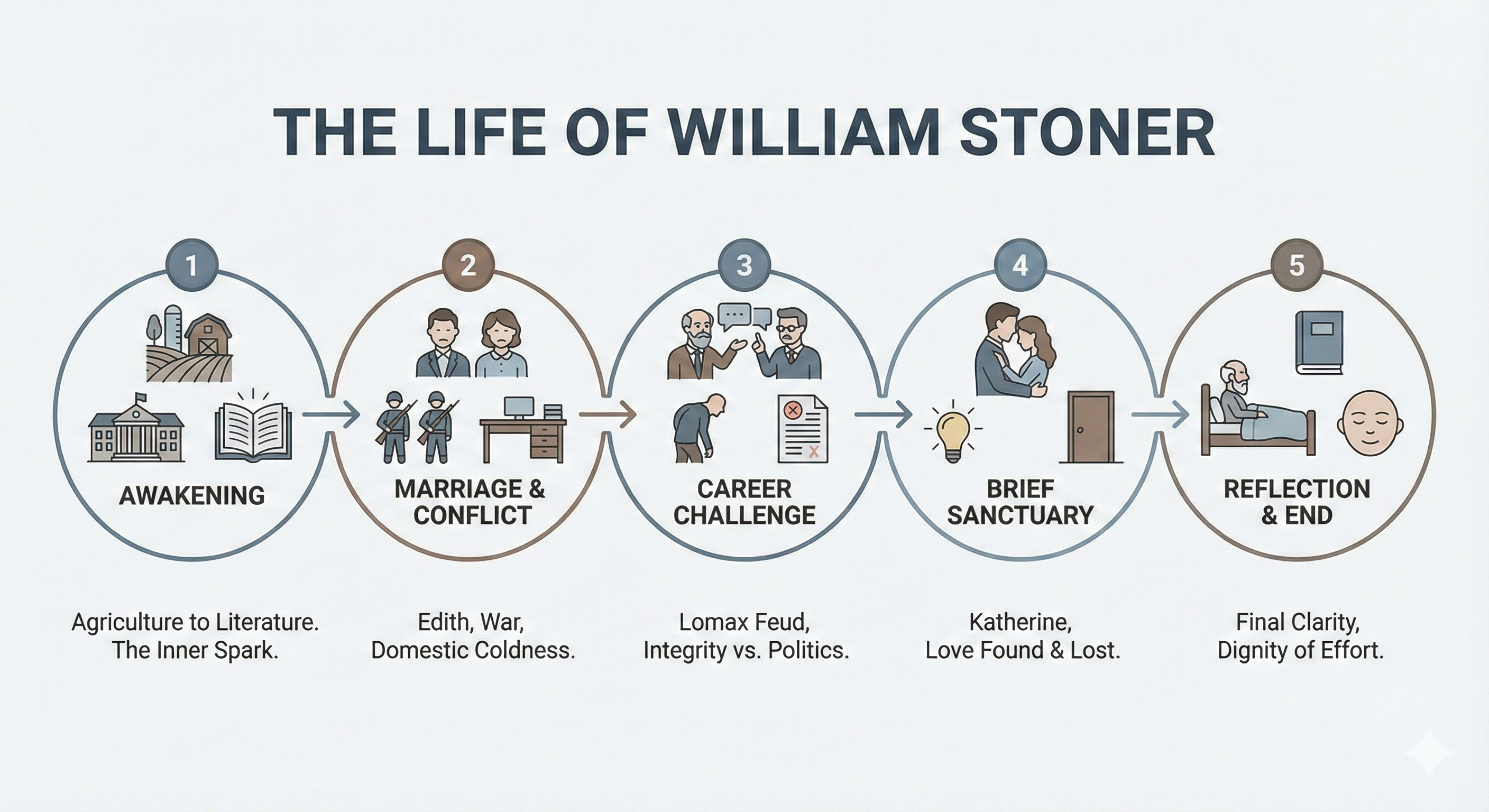

Part I: The Awakening (Chapters 1–4)

The novel begins with a “spoiler”—a cold, factual obituary stating that William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a student in 1910 and taught there until his death in 1956. We are told explicitly that few remembered him. This sets the stage for a forensic examination of a life that left no mark on the world, yet contained a universe within it.

Born to impoverished dirt farmers, Stoner is sent to the university to study Agriculture, intended to bring modern farming techniques back to the family soil. However, in a pivotal scene during a sophomore English literature survey, Stoner is called upon to interpret Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73. Unable to articulate the poem’s meaning but deeply moved by it, he experiences an intellectual awakening. He abandons agriculture for literature, a decision that estranges him from his parents but aligns him with his true self. This section establishes the University as a Sanctuary—a place not just of learning, but of escape from the brutal, mindless necessity of the farm.

Part II: Marriage and War (Chapters 5–8)

Stoner meets Edith Bostwick, a woman from a sheltered, St. Louis banking family. Their courtship is awkward and formal; their marriage is an immediate catastrophe. Edith is revealed to be deeply neurotic, sexually repressed, and waging a silent, psychological war against Stoner.

Simultaneously, World War I breaks out. Stoner’s colleagues, including his close friend David Masters, enlist. Masters, a cynic who paradoxically calls the University an asylum for the “infirm,” is killed in France. Stoner, agonizing over the decision, chooses to stay and complete his degree. This decision haunts him but reinforces his commitment to the academic life. The marriage deteriorates further with the birth of their daughter, Grace. Edith seizes control of the household and eventually of Grace, turning the child against her father and isolating Stoner in his own home. Stoner retreats into his study, cementing the theme of Stoic endurance within domestic tragedy.

Part III: The Walker Incident (Chapters 9–11)

This section introduces the antagonist, Hollis Lomax, a hunchbacked, brilliant, but vindictive professor. The conflict centers on a graduate student named Charles Walker, a lazy and incompetent student whom Lomax favors due to shared physical disabilities and a perceived shared victimhood.

When Walker fails his oral exams, Stoner refuses to pass him, citing intellectual integrity. Lomax views this as a personal attack and prejudice. The resulting feud is bureaucratic and petty, yet high-stakes. It illustrates the politics of small places. Stoner stands his ground, refusing to compromise the standards of the university, even when Lomax becomes the department head and punishes Stoner with terrible teaching schedules for the next 20 years. This is Stoner’s quiet heroism: preserving the sanctity of education against corruption, even when it ruins his career advancement.

Part IV: The Affair (Chapters 12–14)

In his middle age, Stoner meets Katherine Driscoll, a young instructor. They begin an affair that provides the warmth, intellectual companionship, and physical intimacy Stoner has been starved of his entire life. For a brief period, Stoner experiences what life could have been. He learns that he is capable of passion and that he is not a dry husk.

However, the outside world intrudes. Lomax discovers the affair and threatens to ruin Katherine’s career to get to Stoner. To save her work and reputation, Stoner agrees to end the relationship. It is a heartbreaking sacrifice, emphasizing the theme that love, like scholarship, sometimes requires painful renunciation. He returns to his solitude, but he is changed, carrying the memory of that love as a private sustenance.

Part V: The End of the Line (Chapters 15–17)

The final years cover Stoner’s aging, his daughter Grace’s tragic unhappiness (she becomes pregnant, marries quickly, and descends into alcoholism), and his eventual retirement. Stoner develops cancer.

In the final chapter, as he lies dying, he reviews his life. He wonders if it was worth it. He hears the sound of his own breathing and reaches for a book on his nightstand—his own book, written years ago, forgotten by the world but tangible proof of his effort. He realizes that “failure” and “success” are mean, trivial words. He was a teacher; he was a man who loved literature. As he passes away, the book slips from his hand. The ending is not despairing but transcendent; he achieves a final, peaceful clarity.

Main Arguments & Insights

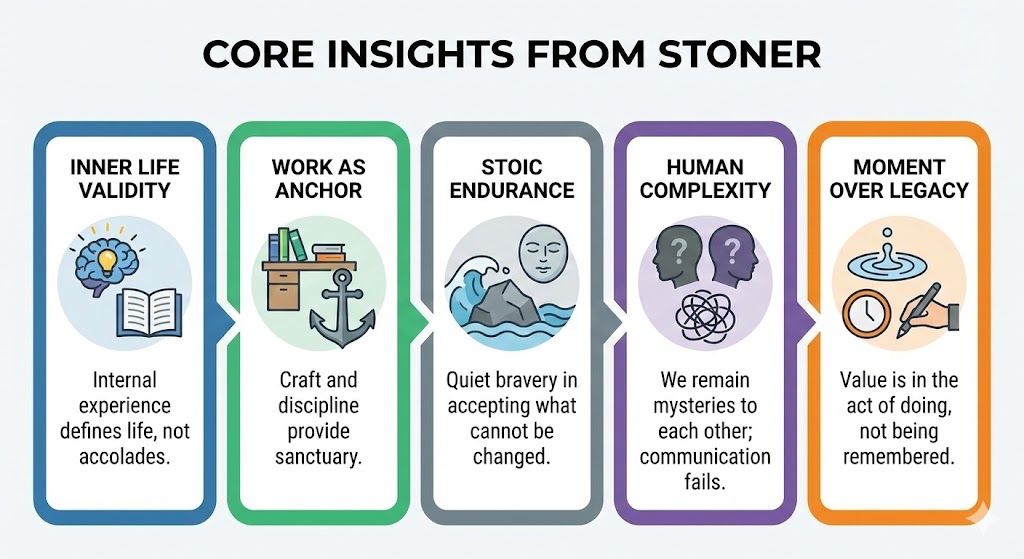

1. The Validity of the Inner Life

Williams argues that a life is not defined by external accolades but by the intensity of one’s internal experience. Stoner’s life appears gray and sad to an observer: a bad marriage, a stalled career, no fame. Yet, inside, he is constantly grappling with the giants of literature, feeling the “terror and beauty” of words. The book validates the introvert’s journey, suggesting that the life of the mind is as dramatic and vital as the life of a soldier or statesman.

2. Work as Identity and Anchor

For Stoner, work is not a job; it is a calling. When his marriage dissolves and his friends die, his teaching and reading remain.

- The Sanctuary: The University is portrayed not just as an institution, but as a secular church—a place where the past is preserved and where truth is pursued for its own sake.

- The Discipline: Stoner finds salvation in the routine of preparation and the act of articulation.

- Insight: Meaning is often found not in happiness, but in competence and dedication to a craft.

3. Stoicism and the “Unlived” Life

Stoner is often criticized for being passive. He rarely fights back against Edith; he doesn’t leave his marriage; he accepts Lomax’s punishment. However, the novel posits this not as weakness, but as a form of Stoicism.

- He accepts the things he cannot change (Edith’s nature, the war, his daughter’s drift).

- He focuses intensely on what he can control: his integrity in the classroom.

- The Argument: There is a quiet bravery in endurance. Walking away is not always the courageous act; sometimes, remaining and enduring without losing one’s soul is the harder path.

4. The Complexity of Human Connection

The characters in Stoner are rarely villains or heroes; they are damaged.

- Edith is not simply evil; she is a product of a repressive upbringing that left her void of identity. Her cruelty is a lashing out from her own emptiness.

- Lomax acts out of a twisted sense of justice and defense of the marginalized, even if his methods are corrupt.

- Williams suggests that we remain mysteries to one another. Stoner never fully understands Edith, nor she him. The tragedy of the book is the inability to communicate, leaving characters isolated in their own perceptions.

5. Legacy is Ephemeral, but the Moment is Real

The opening paragraph tells us Stoner is forgotten. The ending shows him clutching his own book, which no one reads. This seems nihilistic, but the narrative implies the opposite. The fact that he wrote it, the fact that he taught students who then went on to live their lives, matters.

- The Ripple Effect: We may not be remembered by name, but the energy we put into the world—through teaching, parenting, or creating—enters the flow of humanity.

- Insight: We must detach our effort from the expectation of immortality. The value of an act is in the doing, not the remembering.

Critical Reception & Perspectives

The Resurrection of a Classic When Stoner was published in 1965, it sold fewer than 2,000 copies and went out of print within a year. It was a commercial failure, likely because its quiet, academic setting clashed with the counter-cultural, loud zeitgeist of the 1960s.

The Renaissance: In the early 2000s, thanks to champions like the novelist John McGahern and the re-issue by New York Review Books Classics, it exploded in popularity, particularly in Europe. It was named Waterstones Book of the Year in 2013. Critics now universally praise Williams’ “plain style”—prose that is stripped of ornamentation yet glows with emotional precision.

Perspectives:

- The “Perfect” Novel: Critics like Julian Barnes and Ian McEwan have lauded it for its narrative economy and emotional devastation. It is often cited as a perfect example of how to write a life story.

- Critique of Gender: Some modern critics point out the harsh depiction of Edith. She is often viewed as a caricature of the “shrewish wife.” However, others argue that we are seeing her strictly through Stoner’s limited, baffled perspective, which justifies the depiction.

- Passivity: A common criticism is that Stoner is too passive, a “doormat.” However, defenders argue this misses the point of the character’s internal fortitude. He fights for what he values (literature, his student’s grades) and yields on what he deems less essential to his core self.

Real-World Examples & Implications

While Stoner is a work of fiction, its psychological realism offers tangible takeaways for modern life and business:

-

The “Technician” vs. The “Politician”:

-

In the workplace, Stoner represents the pure technician—someone obsessed with the quality of the work itself. Lomax represents the politician. The book illustrates the inevitable friction between meritocracy and office politics. The lesson? Maintaining integrity often comes at the cost of advancement, and one must be willing to pay that price to sleep well at night.

-

Defining Success on Your Own Terms:

-

Stoner dies a “failure” by capitalist standards (low rank, little money). But he dies a “success” by his own standards (he kept the faith with literature). In a “hustle culture,” this is a reminder to define your own KPIs for a life well-lived.

-

The Danger of the “Sunk Cost” in Relationships:

-

Stoner’s marriage is a case study in the sunk cost fallacy. He stays due to propriety and hope, but the toxic environment destroys his daughter. It serves as a grim warning about the costs of conflict avoidance in personal relationships.

-

Deep Work as Refuge:

-

Cal Newport’s concept of “Deep Work” is exemplified here. When Stoner’s life falls apart, he survives by immersing himself in complex texts. This suggests that having a “high-focus” hobby or profession can act as a psychological buffer against life’s chaotic variables.

Suggested Further Reading

-

“The Remains of the Day” by Kazuo Ishiguro

-

Why: A similar exploration of dignity, repression, and a life devoted to service, featuring a protagonist who realizes the cost of his choices late in life.

-

“Revolutionary Road” by Richard Yates

-

Why: Another mid-century American classic that deals with the disintegration of a marriage and the crushing weight of disappointment, though with a much more cynical edge than Stoner.

-

“Letters to a Young Poet” by Rainer Maria Rilke

-

Why: Non-fiction that mirrors Stoner’s philosophy. It advises a young writer to look inward and find the necessity to create, regardless of external fame—essentially the blueprint for Stoner’s life.