Why this book matters

Notes from Underground is frequently cited as the first true existentialist novel: a piercing cry from the margins of society that shattered the optimistic rationalism of the 19th century. Written in 1864, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella introduces us to the “Underground Man,” a nameless, retired civil servant who serves as one of literature’s most complex anti-heroes. This book is not merely a story; it is a philosophical battleground. It matters because it challenges the comfortable assumption that human beings act in their own best interests. It confronts the reader with the uncomfortable truth that humans often crave chaos, suffering, and destruction simply to prove they are free agents, not piano keys to be played by the laws of nature.

The book’s core thesis acts as a rebuttal to the prevailing socio-political theories of Dostoevsky’s time, specifically “rational egoism” and utopian socialism: these theories posited that if society could be organized rationally and humans were enlightened by science, suffering would vanish, and a “Crystal Palace” of perfection would emerge The Underground Man sneers at this, arguing that a man will burn down the palace just to assert his right to do so. In an age of algorithms, data-driven optimization, and the constant pursuit of “happiness,” Dostoevsky’s warning about the irrepressible, irrational nature of the human spirit is perhaps more relevant today than it was in Tsarist Russia.

Chapter by chapter analysis

The novella is distinctively split into two parts: the philosophical monologue of the present and the narrative flashbacks of the past.

Part I: Underground (The Philosophy)

This section is a dense, rambling confession where the narrator introduces himself and his worldview. He is forty years old, sick, spiteful, and unattractive—and he revels in it.

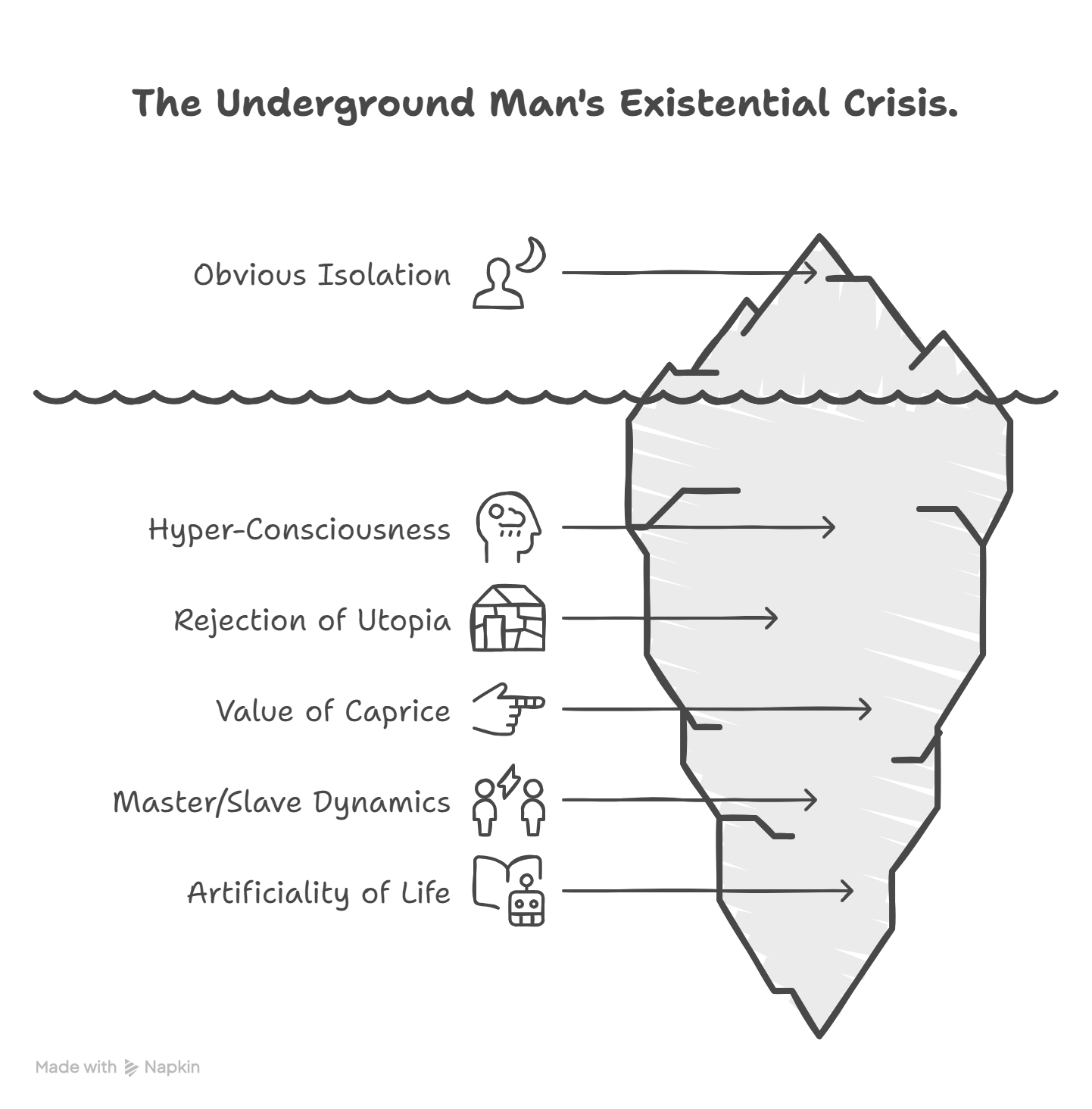

- The Disease of Hyper-Consciousness: The narrator begins by declaring himself a sick man. He distinguishes between the “direct man of action” and the “man of acute consciousness” (himself). The man of action sees a wall (the laws of nature, science, 2+2=4) and stops, accepting it as truth. The Underground Man sees the wall, knows he cannot break it, but refuses to accept it, writhing in resentment against the impossible. He argues that high intelligence inevitably leads to inertia because one sees all the causes and consequences, leading to an inability to act.

- The Enjoyment of Despair: He claims there is a strange, perverse pleasure in a toothache, or in being humiliated. This is the voluptuousness of suffering. It is the only way for a highly conscious man to feel distinct and alive. He admits he was never even able to become truly “wicked”—he is nothing, not even an insect.

- The Critique of Rational Egoism (The Crystal Palace): This is the philosophical heart of the book. The narrator attacks the idea that man only does “dirty tricks” because he doesn’t understand his true interests. He asks: What if it is sometimes in man’s best interest to desire exactly what is bad for him? He uses the metaphor of the Crystal Palace (representing the perfect, rational utopian society) and the “ant-heap.” In such a world, everything is calculated, and there is no free will. The narrator declares he would rather stick his tongue out at the Crystal Palace than live in a world where he is merely a “piano key” played by the laws of physics.

- The Caprice: He concludes that man’s most advantageous advantage is free will—even if that will is destructive. We preserve our personality and individuality by acting against reason.

Part II: À Propos of the Wet Snow (The Narrative)

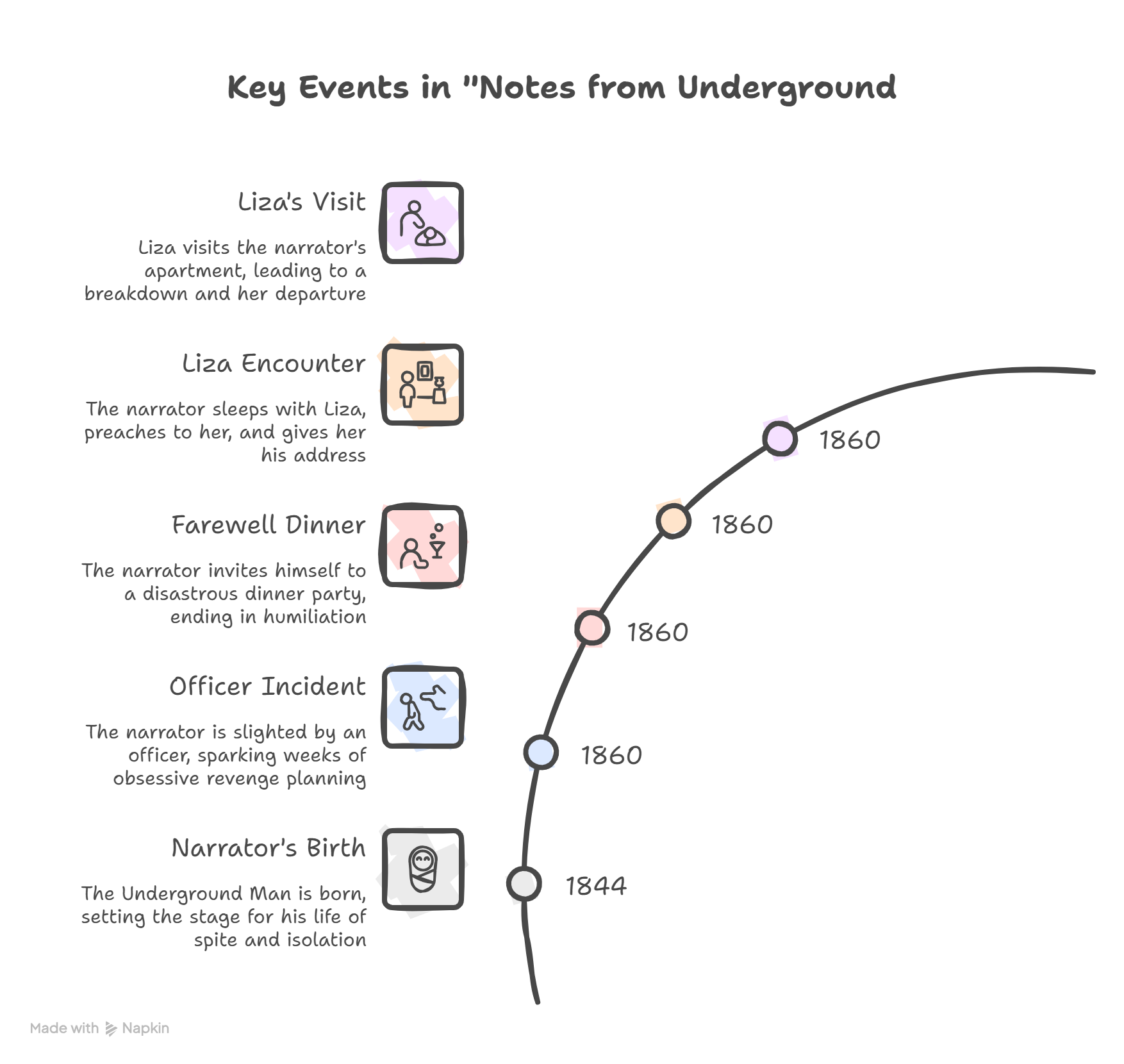

The second part takes place 16 years prior, when the narrator was 24. It serves as a practical example of the philosophy described in Part I, showing the Underground Man’s interactions with the real world.

- The Officer in the Tavern: The narrator feels slighted by an officer who physically moves him out of the way without acknowledging him. Obsessed with revenge and asserting his equality, the narrator spends weeks plotting to bump into the officer on the street. When he finally does, the officer barely notices, but the Underground Man feels a triumphant “moral victory.”

- The Farewell Dinner: The narrator invites himself to a dinner party for Zverkov, a former schoolmate he despises for being popular and successful. The dinner is a disaster. The narrator oscillates between pathetic attempts to win their approval and aggressive insults. He gets drunk, paces the room while the others ignore him, and eventually challenges them to a duel. They leave for a brothel, and he chases after them, fantasizing about slapping Zverkov but also longing for their forgiveness.

- Liza and the Brothel: He arrives at the brothel but the men are gone. He ends up sleeping with Liza, a young prostitute. Afterward, in a fit of “bookish” romanticism, he preaches to her about the horrors of her future and the beauty of family life, reducing her to tears. He gives her his address, playing the role of a savior to boost his own ego.

- The Climax: A few days later, Liza comes to his shabby apartment. The narrator is mortified by his poverty. He realizes he hates her because she witnessed his humiliation at the dinner, and now she sees his squalor. He breaks down in hysteria, confessing that his speech was a lie meant to humiliate her. Instead of recoil, Liza embraces him with compassion. This crushes him—he cannot handle being the recipient of pity; he must be the master. He has sex with her to dominate her, then insults her by thrusting money into her hand. She leaves, dropping the money on the table. He runs after her into the snow, but she is gone. He returns to his “underground,” resigning himself to his solitude and spite.

Main Arguments & Insights

1. The Burden of Hyper-Consciousness

Dostoevsky posits that acute consciousness is a disease. While the “normal” man can act because he believes in the justification of his actions, the hyper-conscious man sees every side of every issue. He falls into an infinite regress of analysis. This leads to inertia. The Underground Man cannot become anything—not a hero, not a villain, not even a sluggard—because his intellect deconstructs every motive until it feels meaningless. He argues that to act, one must be stupid enough to believe in a singular cause, whereas he sees the complexity and contradiction in everything.

2. The Rejection of The “Crystal Palace” (Rational Utopia)

The Underground Man launches a savage attack on the 19th-century ideals of scientific determinism and utopian socialism (symbolized by the Crystal Palace). The prevailing theory was that science would eventually map out human nature so perfectly that crime and suffering would disappear, and life would become a table of logarithms.

- The Argument: If you satisfy all of a human’s material needs and give him a schedule to follow, he will immediately break something or cause chaos just to prove he is not a “piano key.”

- Takeaway: Human beings value autonomy over happiness. We would rather be free and miserable than happy slaves to reason.

3. The “Most Advantageous Advantage”

What is the one interest that contradicts all statistical tables of human happiness? Caprice. The ability to choose the irrational, the stupid, and the harmful.

- The Underground Man argues that all social theories fail because they omit this one factor.

- Man desires to prove his life is his own making. If a formula proved that our whims were inevitable, we would stop being human and become cogwheels. Therefore, the most advantageous thing a man can do is sometimes to act against his own profit, simply to preserve his personality.

4. The Master/Slave Dialectic in Relationships

In Part II, we see that the Underground Man is incapable of interacting with others as equals. He oscillates between feeling like a god and feeling like a bug.

- Tyranny or Subjugation: He notes, “I could not be in love without tyrannizing and without moral supremacy.”

- When he is with his schoolmates, he feels inferior and seeks to degrade them or force them to acknowledge him. When he is with Liza, who is socially inferior, he immediately tries to crush her psychologically to restore his own self-worth. He cannot love; he can only conquer or be conquered.

5. The Artificiality of “Bookish” Life

The narrator constantly admits that his emotions and words are “taken from books.” He has lived in his head for so long, reading European literature and philosophy, that he doesn’t know how to have a real human interaction.

- When he tries to save Liza, he uses flowery, sentimental language he “stole” from romantic novels.

- When reality hits (Liza’s genuine love and pity), his bookish script fails him. He retreats into cruelty because reality is messy, whereas the “Underground” (his isolated mind) is safe and controlled.

Critical Reception & Perspectives

Initial Reception: Upon its publication in 1864, Notes from Underground was met with confusion. It was a radical departure from Dostoevsky’s earlier, more socially focused works. The Russian censors also removed key passages where the narrator hinted at a need for religious faith, leaving the text more bleak and cynical than Dostoevsky originally intended. Contemporary critics saw it as a harsh caricature of the “superfluous man” or a specific attack on the socialist novel What Is to Be Done? by Chernyshevsky.

Existentialist Canon: The book found its true appreciation in the 20th century. Friedrich Nietzsche discovered Dostoevsky through this book and called it a “stroke of genius,” identifying an immediate kinship with the psychology of the Underground Man. Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus later embraced it as a precursor to existentialism. The concept of the “Anti-Hero”—a protagonist lacking traditional heroic qualities like courage or morality—owes its modern popularity largely to this novella.

Modern Criticism:

- Praise: It is lauded for its psychological depth. The description of the “spiteful” mind is considered one of the most accurate depictions of neurosis and self-loathing in literature.

- Critique: Some critics argue that the book is too dense and ideologically heavy in Part I. Others point out that the Underground Man is so repulsively narcissistic that it is difficult for readers to engage with him, though this feature is intentional. A valid limitation noted by scholars is that without the context of the Russian philosophies Dostoevsky was attacking (Rational Egoism), the first half can seem like the ramblings of a madman rather than a structured philosophical rebuttal.

Real-World Examples & Implications

-

The Psychology of Self-Sabotage:

-

The Underground Man explains why we procrastinate, why we stay in bad relationships, or why we ruin moments of happiness. It is often an unconscious assertion of control. If I ruin my own life, at least I am the one doing it.

-

The Failure of Corporate “Culture”:

-

Modern attempts to engineer perfect employee happiness or strict productivity workflows often fail. As Dostoevsky predicted, people resist being “optimized.” Employees may rebel against micromanagement not because the management is wrong, but simply to assert agency.

-

Internet Trolls and “Incels”:

-

The Underground Man is the archetype of the modern internet troll. Isolated, intelligent but socially inept, resentful of the “Zverkovs” (Chads) and “Lizas” (women) of the world, he lashes out from behind the safety of his “underground” (the screen). His mixture of superiority and inferiority complexes perfectly mirrors the psychology seen in toxic online communities.

-

Critique of AI and Algorithmic Determinism:

-

In an era where algorithms predict what we want to buy, watch, and who we want to date, this book serves as a warning. We may eventually resent the “perfect” recommendations of the algorithm (The Crystal Palace) and choose the “wrong” option just to prove we are not data points.

Suggested Further Reading

-

**** “Crime and Punishment” by Fyodor Dostoevsky

-

An expansion of the “Great Man” theory and the psychological toll of rationalizing evil, featuring a protagonist (Raskolnikov) who shares the Underground Man’s isolation but attempts to act on it.

-

**** “The Stranger” (L’Étranger) by Albert Camus

-

Explores the absurd and the indifferent, offering a different take on the alienated anti-hero who, unlike the Underground Man, feels nothing rather than everything.

-

**** “Nausea” by Jean-Paul Sartre

-

A direct descendant of Notes, this diary-format novel deals with “Roquentin,” a historian who is overcome by the physical sensation of existence and the absurdity of the world.

-

“Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison

-

Heavily influenced by Dostoevsky, this novel explores the social and racial “underground” of an African American man, dealing with similar themes of visibility, identity, and social blindness.

Final Thought

Notes from Underground is not a book to be “enjoyed” in the traditional sense; it is a mirror to be endured. It forces us to confront the ugly, irrational, and spiteful parts of our own psyche that we usually hide behind logic and social niceties.