Why this book matters

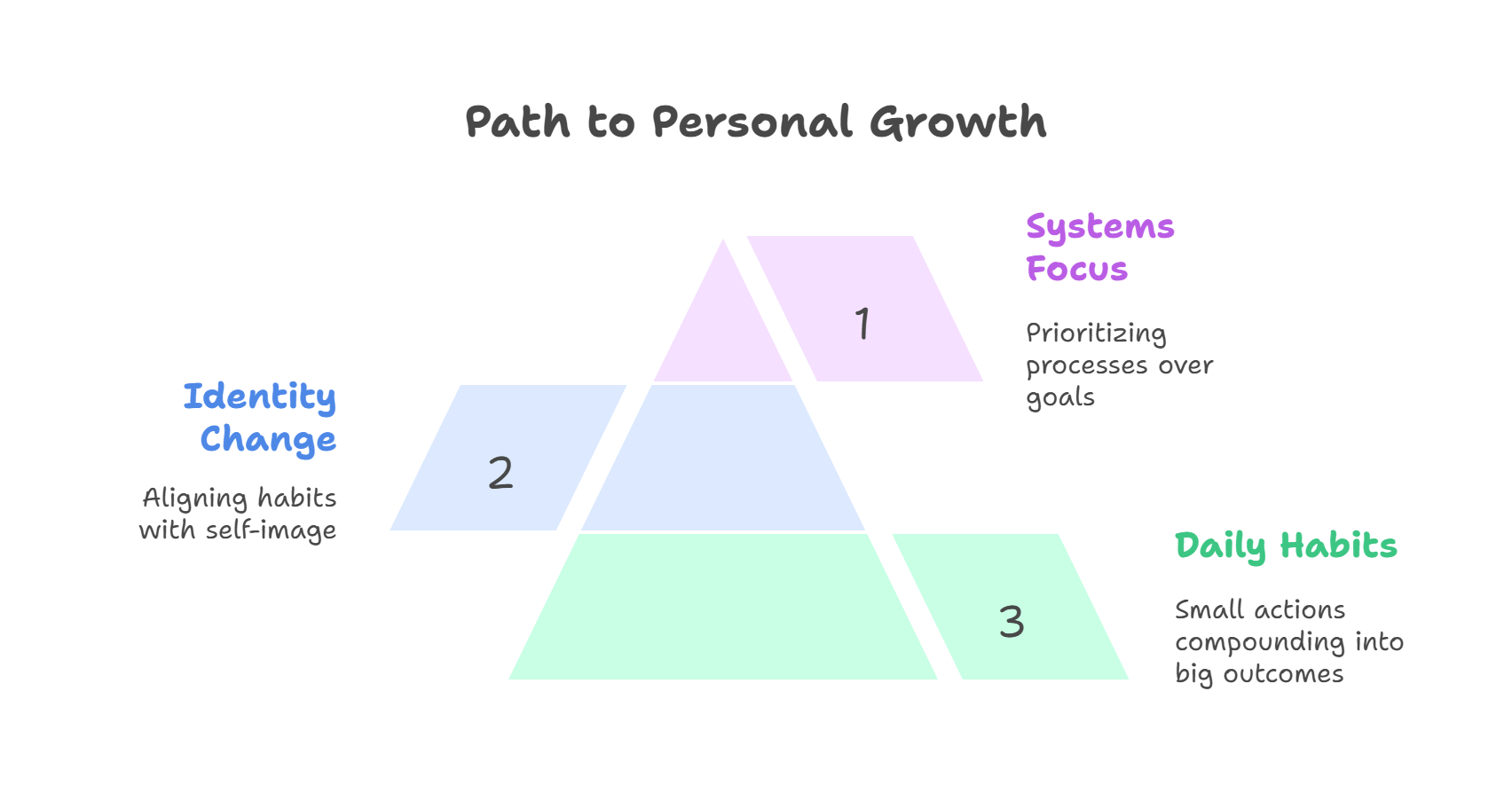

James Clear’s Atomic Habits matters because it reframes self-improvement from grand resolutions into small, consistent behavioral changes that compound over time. In an era obsessed with quick fixes and dramatic transformations, Clear offers a grounded, evidence-informed approach that emphasizes systems over goals, identity over outcomes, and environment over willpower. His framework empowers individuals to take control of their habits not through motivation alone, but through intentional design of cues, routines, and rewards.

The book’s real significance lies in its practical applicability across contexts—from personal health to professional productivity, from education to public policy. It bridges behavioral psychology and real-world action in a way that is accessible without being superficial, making it a foundational text in the modern habit-change movement. With over 20 million copies sold and influence across industries, Atomic Habits has helped millions recognize that lasting change starts small—but must be intentional. It’s not just a guide to better habits—it’s a manual for building a better identity, one tiny improvement at a time.

Chapter by chapter analysis

-

Chapter 1: The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits – Introduces the idea that tiny daily habits compound into remarkable long-term results. Clear illustrates this with the “1% better every day” concept – over a year, a 1% daily improvement leads to being 37 times better. He uses the success of British Cycling under coach Dave Brailsford to show how aggregating many small 1% gains (from better bike seats to painted floors) led to Olympic gold medals. The chapter’s key message is that habits are the “compound interest” of self-improvement and that massive success doesn’t require massive action at once, but consistent incremental progress.

-

Chapter 2: How Your Habits Shape Your Identity (and Vice Versa) – Explores the deep link between identity and habits. Clear argues that lasting behavior change is really identity change – you must see yourself as the kind of person who embodies the habit. He suggests focusing on who you wish to become rather than on specific outcomes. For example, “the goal isn’t to run a marathon, it’s to become a runner”. By “casting votes” for your desired identity with each small habit, you reinforce that identity. In essence, each habit is a vote for the type of person you want to be.

-

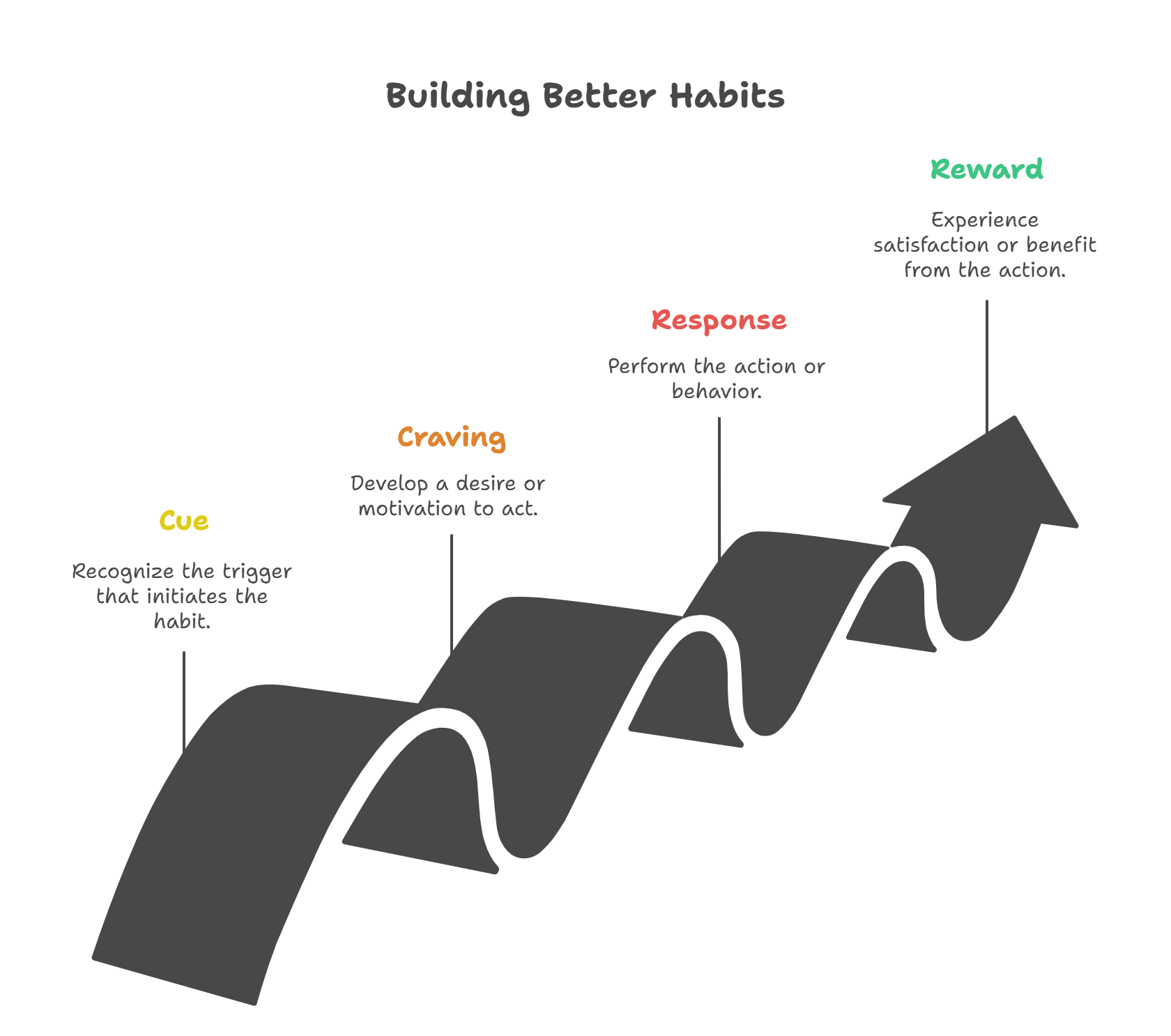

Chapter 3: How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps – Lays out the fundamental habit loop and Clear’s framework for behavior change. Every habit, he explains, consists of cue, craving, response, and reward. This four-step loop is the backbone of habit formation. Clear then introduces his overarching “Four Laws of Behavior Change” – practical rules to build good habits (and invert to break bad ones): Make it obvious, Make it attractive, Make it easy, Make it satisfying. These principles follow from the habit loop (e.g. cues should be obvious, rewards satisfying) and set the stage for the rest of the book.

-

Chapter 4: The Man Who Didn’t Look Right – Emphasizes the power of cues and automaticity in habit formation. Clear shares the story of Eugene Pauly, a man with memory loss who still formed habits by repetition. This dramatic example shows that habit cues can trigger actions even without conscious memory – our brains automate routines through context cues. The key takeaway is that much of our behavior is driven by habit loops operating below awareness, so designing the right cues is critical.

-

Chapter 5: The Best Way to Start a New Habit – Introduces practical strategies for initiating new habits. Clear advocates “habit stacking,” which means attaching a new habit to an existing one so that the current routine cues the next behavior. For example: “After I brew my morning coffee (current habit), I will meditate for one minute (new habit).” By piggybacking on established routines, you leverage the momentum of existing habits. This chapter also suggests making a specific plan (an implementation intention) like “I will [NEW HABIT] at [TIME] in [LOCATION]” to make the habit’s cue obvious and actionable.

-

Chapter 6: Motivation Is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More – Argues that environment design beats sheer willpower in shaping behavior. Clear contends that our habits are largely a product of our surroundings rather than intrinsic motivation or genetics. He advises making good habit cues visible and convenient (e.g. put healthy snacks at eye level) and making bad habits invisible (hide temptations). Small changes in context – like decluttering a workspace or placing a guitar in the center of the room to practice – can dramatically impact habit adherence. The lesson: “It’s easier to avoid temptation than to resist it,” so structure your environment to favor the behaviors you want.

-

Chapter 7: The Secret of Self-Control – Explores how to sustain good habits by reducing reliance on brute self-control. Clear explains that people with strong self-control aren’t necessarily more disciplined in the moment – rather, they structure their lives to require less willpower. The “secret” is often to remove the cues of bad habits in advance (for example, don’t keep junk food in the house if you want to eat healthy). By redesigning your environment and routine to minimize exposure to temptations, you won’t need heroic willpower as often. This chapter reinforces that self-control can be “outsourced” to your environment, aligning with the idea that avoiding triggers is more effective than constantly fighting impulses.

-

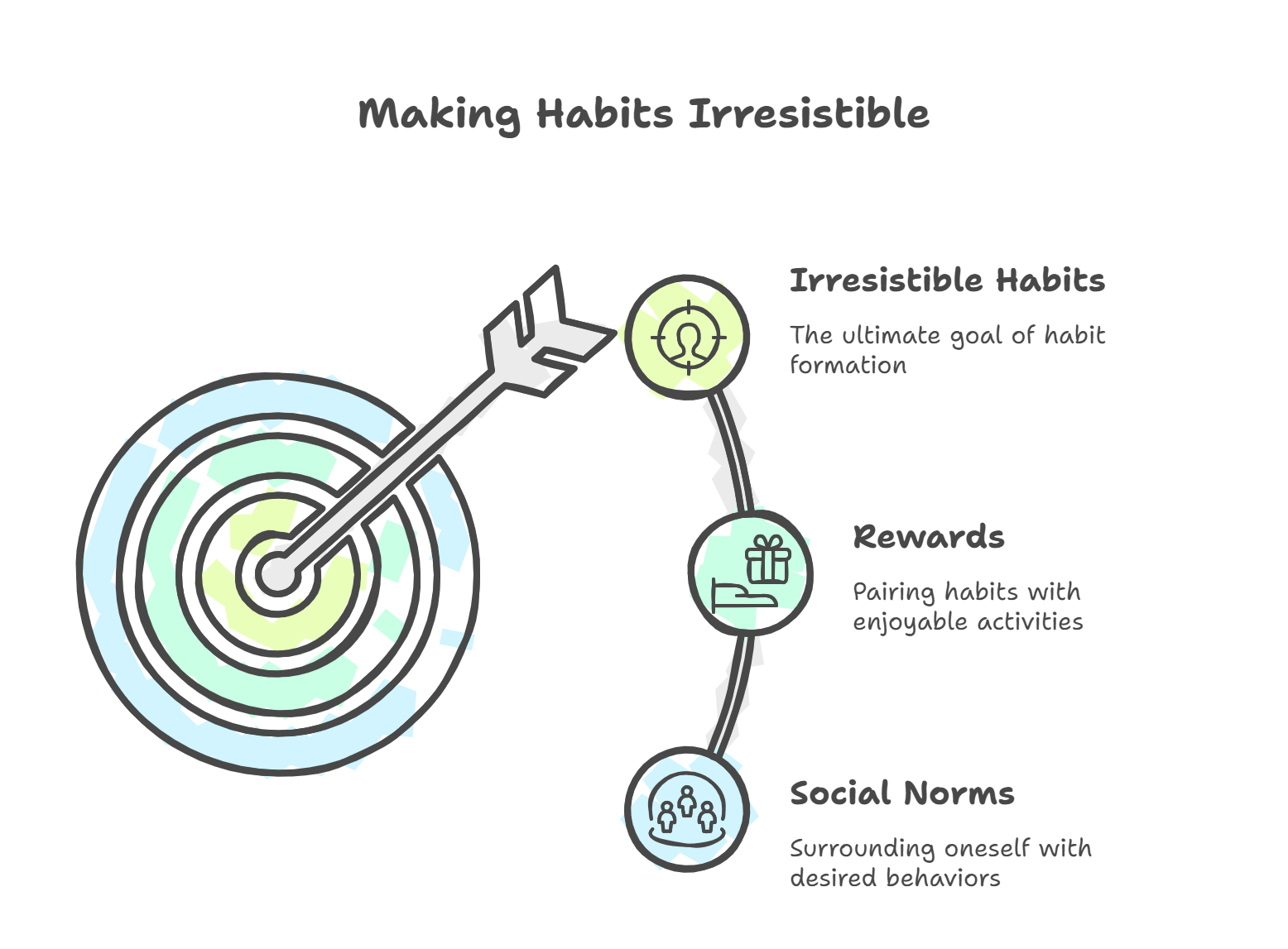

Chapter 8: How to Make a Habit Irresistible – Begins Part II (the 2nd Law: Make It Attractive) by focusing on increasing a habit’s appeal. Clear suggests leveraging the brain’s reward system – e.g. pair habits with things you enjoy or use temptation bundling (only do a fun activity while doing the habit you need to do). He also notes the power of social norms: making habits attractive by surrounding yourself with people who already exhibit the desired behavior. For instance, joining a class or club where the habit is the norm provides positive social reinforcement. The core idea is that if you find ways to make a habit more enticing (through rewards or social incentive), you’re more likely to repeat it.

-

Chapter 9: The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits – Delves into the social dimension of habits. Clear explains that our peer group influences our behavior profoundly. We tend to imitate the habits of “close, many, and powerful” – meaning our family and friends, the broader tribe, and those with status. To build better habits, he advises choosing environments where your desired behavior is normal. For example, if you want to exercise, spend time with fit friends or join a fitness community. By aligning with a supportive social circle or culture, you benefit from conformity in a positive way. Conversely, be mindful that certain social environments can reinforce bad habits.

-

Chapter 10: How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits – Investigates how to break bad habits by understanding their triggers. Clear recommends performing a kind of habit autopsy: identify the cue, craving, reward driving the unwanted behavior. Once you pinpoint the cues (maybe stress triggers a junk food snack) and the reward you’re really seeking (comfort, distraction, etc.), you can find healthier alternatives to satisfy the same craving. He suggests inverting the earlier principles for breaking bad habits – e.g. make the cues invisible, make the habit unattractive, difficult, and unsatisfying. By removing triggers and adding friction or cost to your bad habits (for example, delete tempting apps or require extra steps to access a vice), you can interrupt the habit loop and replace it with better behaviors.

-

Chapter 11: Walk Slowly, but Never Backward – Kicks off Part III (the 3rd Law: Make It Easy) by emphasizing consistency over perfection. Clear’s message here is to focus on getting reps in, even if progress is slow. He notes that small, sustainable actions beat infrequent extreme efforts. The chapter title suggests that as long as you keep moving forward (no matter how slowly), you’re doing fine. Consistency compounds – missing a day is okay, but never miss twice in a row if you can help it. The key takeaway is that continuous, even tiny improvements accumulate, whereas stopping altogether loses the benefit. In short, prioritize showing up regularly for your habits, and accept slow growth over backsliding.

-

Chapter 12: The Law of Least Effort – Explains that human behavior follows the law of least resistance, so we naturally gravitate toward the easiest option. Clear applies this insight to habit-building: to foster a good habit, reduce the friction and difficulty required to do it. For example, prep your workout clothes the night before, or keep healthy food readily available – anything to streamline the desired behavior. He also mentions using automation and technology to your advantage (such as apps or automatic savings transfers) so that some positive actions happen with minimal effort. The easier a habit is, the more likely you’ll do it; thus, design your environment and routines so that the “path of least effort” leads to your good habits.

-

Chapter 13: How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule – Introduces the “Two-Minute Rule,” a tactic to overcome procrastination and build momentum. The rule is: when you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do. By scaling habits down to a very easy, quick start, you lower the barrier to beginning. For instance, “read one page” or “put on running shoes” are two-minute versions of bigger goals (reading an hour, running 5K). Once you’ve started, you often continue beyond two minutes – but even if not, you’ve kept the habit alive. Clear explains that the greatest obstacle is often simply starting, and this rule ensures you start in a manageable way. This strategy turns big goals into tiny actions that feel trivial to do, thereby defeating the inertia of procrastination.

-

Chapter 14: How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible – Discusses using commitment devices and environment design to lock in good habits. The idea is to “raise the stakes” so that not doing the right thing becomes difficult, and doing the wrong thing becomes difficult. Clear suggests creating an environment where good habits are the default – for example, remove batteries from the TV remote to make watching TV less convenient, or schedule a gym class with a nonrefundable fee. He also cites examples of people who made bad habits impossible (like a student who cut the internet cord each night to stop late-night browsing). On the flip side, you can make good habits inevitable by removing obstacles – e.g. sleep in your workout clothes to ensure you exercise in the morning. In short, engineer your future choices: “lock in” favorable behaviors and put bad ones on lockdown.

-

Chapter 15: The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change – Opens Part IV (the 4th Law: Make It Satisfying) by revealing the crucial principle that behaviors need to feel immediately rewarding to stick. Clear’s “cardinal rule” is essentially that if a behavior is satisfying, we have a reason to repeat it. He recaps the Four Laws (make it obvious, attractive, easy, satisfying) as a holistic recipe for successful habit formation. This chapter underscores the importance of reward and positive reinforcement. For building good habits, that means finding ways to give yourself a small instant reward (even if just a sense of accomplishment or a check on a habit tracker) after the behavior. For breaking bad habits, it means removing any immediate pleasure (making them unsatisfying). The principle is drawn from behavioral psychology: behaviors that get rewarded get repeated. Thus, finding a way to feel good after a habit – even something simple like ticking off a calendar – helps lock it in.

-

Chapter 16: How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day – Focuses on maintaining consistency in the long run. Clear provides several strategies: use a habit tracker or log to create a visual cue of your progress (the satisfaction of streaks can be its own reward), employ the “never miss twice” rule to recover quickly from any slip-up, and focus on the process rather than the outcome. He also encourages celebrating small wins to keep habits satisfying. This chapter addresses common challenges like travel or illness disrupting routines, advising to get back on track as quickly as possible (hence never missing twice). The key takeaway is that habits are a daily practice, and using tools like tracking, accountability, and a positive mindset will help you stick to your habits day in and day out.

-

Chapter 17: How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything – Highlights the power of social accountability in habit formation. Clear suggests that pairing up with someone – an accountability partner or group – can dramatically increase your adherence to a habit. When you share your goals and progress with someone, you benefit from support and a sense of obligation. The chapter describes how an accountability partner can provide encouragement, feedback, and a bit of healthy pressure to keep you on track. Whether it’s a workout buddy, a study partner, or just regularly reporting your progress to a friend, knowing someone else is watching your behavior can be a powerful motivator. This ties into the broader theme that habits aren’t just individual – they can be strengthened through social commitments and external checks.

-

Chapter 18: The Truth About Talent (When Genes Matter and When They Don’t) – Begins the “Advanced Tactics” section by examining the interplay of talent, genetics, and habits. Clear discusses that while genetics can influence our natural inclinations or advantages, habits and deliberate practice are what unlock potential. He encourages readers to tailor habits to their own nature – i.e. choose habits that best suit your personality and talents (your genetic advantages) for greater success. For example, if you have a naturally high endurance, building a running habit might come easier and yield better results than a powerlifting habit. However, he stresses that effort, consistency, and continuous improvement matter more than innate talent in the long run. The key insight is that genes don’t eliminate the need for good habits; rather, good habits will take you farther than talent alone, and anyone can improve by working steadily at the right things.

-

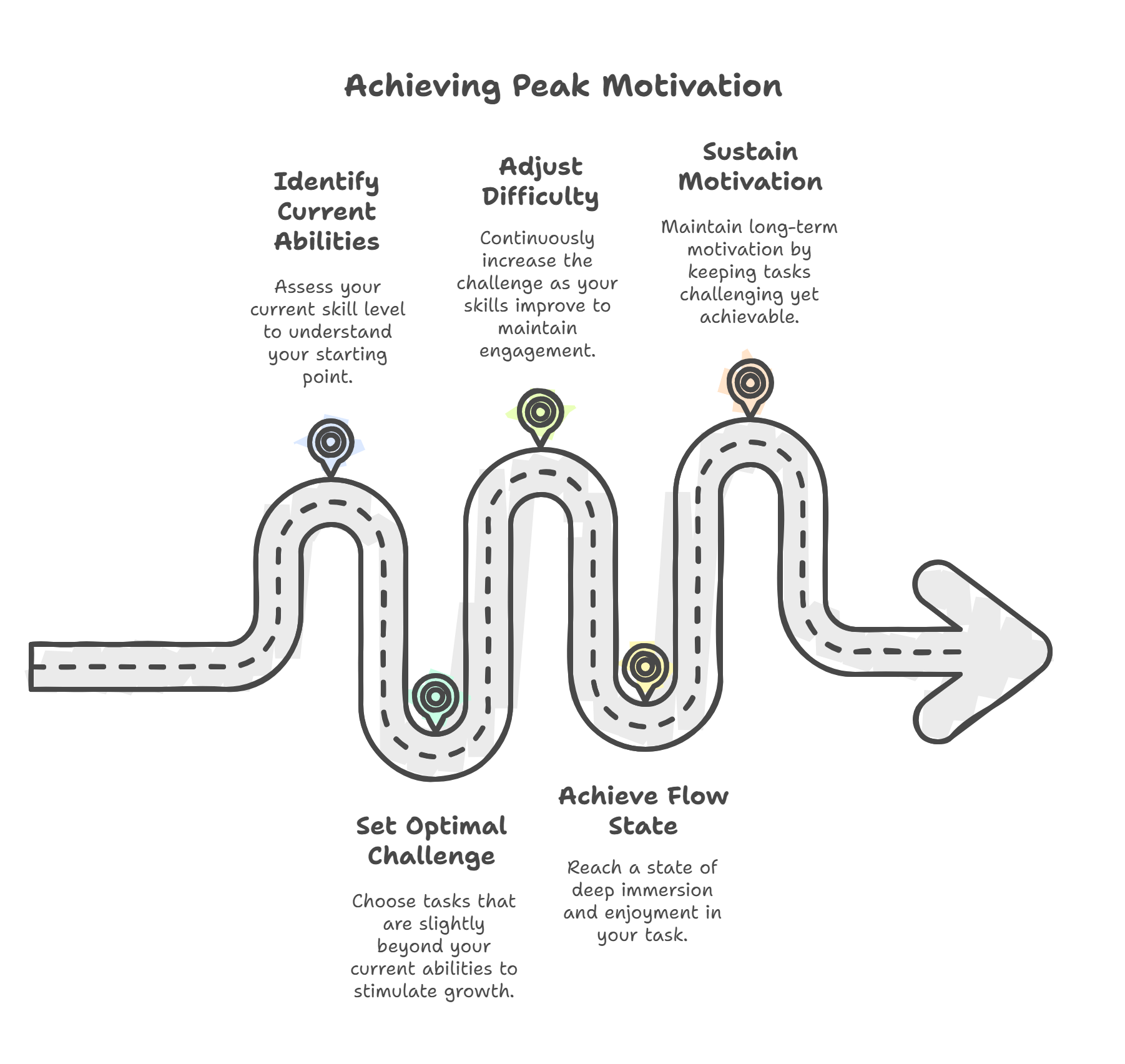

Chapter 19: The Goldilocks Rule – How to Stay Motivated in Life and Work – Addresses the challenge of staying motivated by finding tasks that are just right in difficulty. The Goldilocks Rule states that people experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right at the edge of their current abilities – not too easy (which is boring) and not too hard (which is discouraging). Clear explains that to avoid losing interest in your habits, you should continually adjust the challenge as you improve, keeping it in that optimal zone. For example, if you’re learning a language, continually increase the difficulty of material as your skills grow, so you remain engaged. This concept also ties to the idea of flow state in psychology – the state of being fully immersed in an activity that’s suitably challenging. The takeaway is to keep your habits challenging enough to be stimulating but achievable enough to be rewarding, thereby sustaining your motivation over the long haul.

- Chapter 20: The Downside of Creating Good Habits – Concludes the main chapters by warning that even positive habits have potential pitfalls. Clear notes that once a habit is established, it runs on autopilot, which can lead to diminishing mindfulness or creativity. The “downside” is that you might get too rigid or stuck in a routine, becoming unwilling to adapt or try new approaches. Additionally, there’s a risk of hitting a plateau – doing something out of habit without continued improvement (what he calls the “plateau of latent potential” earlier in the book). Clear advises readers to review and refine their habits periodically to ensure they still serve their goals, and to avoid the trap of “good enough” becoming an enemy of growth. In essence, while good habits are powerful, one must remain flexible and open to change so that habits continue to serve you as circumstances evolve.

Concluding Chapter: “The Secret to Results That Last.” – In the final summary of the book, Clear reiterates that small habits, sustained over time, lead to remarkable results. He encourages focusing on the process of continuous improvement and embracing the identity of a person committed to those habits. Rather than chasing rapid transformation, the secret is to fall in love with boredom – to master the art of showing up day after day. By this point, the reader is reminded that real change comes from the cumulative effect of hundreds of tiny decisions and actions, and that by aligning your habits with the person you want to be, you can achieve lasting change. The book closes on an optimistic note that anyone can improve by making small, consistent changes, and that these atomic habits are the building blocks of transformative results.

Main Arguments & Insights

1. Habits as the Compound Interest of Self-Improvement: The book’s central premise is that small daily habits compound over time into big outcomes. Just as money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply as you repeat them. This means success is not one big leap but the sum of tiny steps. Clear emphasizes focusing on getting 1% better each day – an idea illustrated by the dramatic payoff of marginal gains (like the British cycling team’s story). The insight is that slow, incremental progress is immensely powerful, even if the gains are not immediately visible. Over months and years, these tiny improvements build on each other, whereas tiny declines also accumulate to destructive effect. This reframing encourages readers to value consistency and patience, trusting that minor improvements will compound into noteworthy results.

2. Identity-Based Behavior Change: A recurring theme is that true behavior change is identity change. Clear argues that we are more likely to stick with habits that align with our self-image. Thus, the book suggests shifting your focus from outcomes to identity. For example, instead of saying “I want to quit smoking,” one should say “I am not a smoker” – adopt the identity of a non-smoker. Each small habit is presented as a “vote” for the type of person you want to become. Over time, your actions provide evidence for this new identity, which reinforces the behavior in a virtuous cycle. This idea – encapsulated in the quote “Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become” – is a cornerstone of Atomic Habits. The book’s insight is that lasting change comes from seeing yourself in a new light (e.g. as a “runner,” “reader,” or “healthy person”) and that small wins help lock in that identity. By focusing on identity, you tap into intrinsic motivation; your habits become an extension of who you are, not just tasks you force yourself to do.

3. Systems Over Goals: Clear makes a compelling case that while goals are good for setting a direction, systems are what drive progress. A goal is an outcome (run a marathon, write a book), but a system is the collection of habits and processes that lead to that outcome (a training schedule, a daily writing routine). The book argues that achieving a goal is a momentary change – if you don’t change the system that led to the result, you risk backsliding. In Clear’s words: “You do not rise to the level of your goals, you fall to the level of your systems.”. This aphorism encapsulates the idea that consistent habits (a system) are more reliable than willpower or lofty goals alone. For example, many people set the goal of “getting in shape,” but those who succeed have a system of exercise and diet habits. Clear’s insight is to focus on building a better system (the daily habits, the environment, the routine) and the outcomes will follow as a natural result. This shifts one’s mindset from obsessing over distant targets to mastering the daily process – something within one’s control. It’s a call to “forget about goals, focus on systems” as the more sustainable path to improvement.

Critical Reception & Perspectives

Atomic Habits was published in 2018 to strong commercial success and generally positive initial reviews, though it has also faced some pointed criticism from experts and journalists. On the positive side, many praised the book’s practicality and clear framework. It became a long-running bestseller – as of early 2024 it had sold nearly 20 million copies and spent over 160 weeks atop the New York Times best-seller list. Readers often credited the book with tangible improvements in their lives. For example, Business Insider profiled an entrepreneur who applied Clear’s methods to beat procrastination and reported a “100% success rate” in using the book’s lessons to become more productive. The Independent (UK) ran a piece titled “James Clear’s Atomic Habits has changed the course of my year,” echoing a common sentiment that the book’s advice is life-changing in practice. The consensus among many self-improvement enthusiasts is that Atomic Habits distills effective habit-building strategies into an accessible, actionable form. Its catchy maxims (like “1% better every day”) and simple diagrams have been widely shared on social media, to the point that a Forbes writer noted the book “caught fire” and its quotes have “broken the internet” with viral popularity.

However, not all critics were convinced. A number of reviewers took issue with what they saw as oversimplification or lack of originality. In a sharp critique, The Guardian’s Steven Phillips-Horst argued that James Clear is essentially repackaging familiar ideas with slick jargon – noting, for instance, that “stacking” simply means doing one thing after another, and “temptation bundling” means giving yourself a treat for doing a task. He lampooned some of the book’s examples as almost comically obvious, such as explaining that turning on a light satisfies a craving for visibility (“my insatiable lust for vision,” he quipped). This review and others in a similar vein describe Atomic Habits as “TedTalk psychology” – engaging and feel-good but not very deep. Critics also targeted Clear’s use of science. The Guardian piece pointed out that Clear occasionally cites dubious-sounding facts (for example, a claim about higher oxytocin levels making people more habit-prone to writing thank-you notes) and leans on qualifiers like “you can imagine” instead of hard evidence. In this view, the book’s scientific veneer is thin, relying more on anecdote and common sense than breakthrough research.

Academic and expert reviewers similarly had mixed perspectives. Many behavioral scientists acknowledged Clear’s talent for communication but felt the book glosses over complexities. For instance, building habits in real clinical populations or addressing addictions involves deeper issues than the book’s simple four-step framework can address. Some psychologists argued that Atomic Habits focuses heavily on external cues and outcomes while downplaying internal factors like emotions, mindset, or underlying mental health challenges. An article on habit change in Slate questioned, “Does it work – and will it be for the better?” suggesting a cautious take on whether one can so straightforwardly engineer one’s life, or if there might be unintended side effects to obsessing over constant self-optimization. And on the writing style, even sympathetic readers noted a certain repetitive, blog-post quality to the chapters – unsurprising given Clear’s background as a prolific blogger. The popular podcast If Books Could Kill went further, calling the writing “gratingly repetitive” and the content a string of platitudes, albeit “very easy to read”.

In summary, the critical reception splits into two camps. Enthusiasts applaud the book for its clarity and usefulness – it’s often cited alongside classics like The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People as a top-tier self-help book, and it enjoys a near-cult following among productivity circles. Skeptics, on the other hand, see it as self-help lite: nothing fundamentally new, and possibly oversold with a slick marketing sheen. They worry that some claims are not rigorously supported and that the book gives a false impression that anyone can completely control their outcomes if they just try hard enough to adopt the right habits. Despite these critiques, even many skeptics concede that Atomic Habits contains sound, if basic, advice – essentially retooling known behavioral principles into a digestible guide. The disagreements, therefore, are less about whether the habits approach works (it often does), and more about how novel, scientific, or universally applicable the book truly is. This tension is perhaps best captured by the Wikipedia summary: “The book received acclaim from most critics, with a few strongly disapproving of its claims”. In other words, Atomic Habits has become both highly influential and somewhat controversial in the self-help genre, loved by millions of readers, yet scrutinized by some who challenge its simplicity and scientific heft.

Real-World Examples & Implications

Clear’s principles in Atomic Habits have resonated widely, and we can see their implications in various real-world domains – from sports and business to personal lifestyles:

-

Elite Sports and the “Marginal Gains” Strategy: One of the book’s striking examples (drawn from real life) is the transformation of British Cycling under Sir Dave Brailsford. By applying a philosophy of “the aggregation of marginal gains” – improving every tiny aspect of training, equipment, and routines by 1% – the British team went from mediocrity to dominating the Olympics and Tour de France. This real-world case epitomizes the book’s message that small habits can yield extraordinary outcomes. Teams in various sports have since invoked similar “atomic habits” approaches: e.g. basketball and rugby coaches focusing on small fundamentals, or swimmers tweaking their diet and sleep routines. The success of marginal gains in sports has even influenced business management; many companies now talk about making continuous 1% improvements in processes (sometimes calling it “Kaizen” or continuous improvement), reflecting Clear’s influence beyond individual self-help.

-

Workplace Productivity and Team Culture: In offices and organizations, Atomic Habits has inspired a focus on habit-building for productivity and innovation. For instance, some software teams have instituted daily “stand-up meetings” or code review habits to incrementally improve output. Managers encourage employees to design their work environment – such as keeping phones in a drawer to break the habit of constant checking, or using website blockers to enforce focus periods. The idea of habit stacking has been applied to workflow (e.g., after sending a daily report email, then take 5 minutes to plan the next day). Clear’s notion of identity-based habits can translate into company culture: organizations identify as “continuous learning” cultures and encourage employees to adopt the identity of learners (e.g. reading a little each day, sharing knowledge). Some firms even run Atomic Habits workshops or book clubs, reinforcing the ideas collectively. The implication is that small habitual behaviors in aggregate determine organizational performance, so shaping those habits at the team level (meeting routines, feedback loops, etc.) can lead to big improvements in efficiency and morale.

-

Personal Finance and Health: Many people have applied Atomic Habits to daily finances and health routines. For example, the habit of saving a tiny percentage of each paycheck automatically can grow into substantial savings over time – a direct parallel to 1% compounding. Financial advisors often stress automatic contributions or “round-up” savings programs, effectively creating habits that run in the background. On the health front, readers have reported using habit stacking to, say, integrate exercise or stretching into their day: “After I brew my morning coffee, I will do 10 push-ups,” turning a small action into a solid fitness habit. The book’s influence is seen in the rise of habit tracking apps and journals in the wellness market. Clear himself launched the “Clear Habit Journal,” a guided journal that helps people track and reflect on their habits. The popularity of fitness streaks (like hitting 10,000 steps daily) or meditation streaks on apps like Headspace can be tied to the satisfying feeling of continuous progress that Atomic Habits advocates. The broader implication is a cultural shift towards viewing self-improvement as a daily systems game – people are less likely now to seek a crash diet or a sudden windfall, and more likely to think in terms of gradually building healthier eating habits, exercise habits, spending habits, etc. This long-term mindset (“small changes, big results”) has arguably made self-improvement efforts more sustainable.

Suggested Further Reading

If Atomic Habits piqued your interest in habits and behavior change, there are several excellent books and resources that delve deeper or offer complementary perspectives:

-

The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg (2012) – A seminal book that predates Atomic Habits, Duhigg’s work explores the habit loop of cue-routine-reward in depth. He illustrates how companies and individuals have leveraged habit science (from Febreze’s marketing to personal habit transformations) and offers a framework for changing habits by identifying cues and rewards.

-

Tiny Habits by B.J. Fogg (2019) – Behavior scientist B.J. Fogg offers a approach very much in harmony with Atomic Habits, but with extra emphasis on starting extremely small and celebrating immediately.

-

Better Than Before by Gretchen Rubin (2015) – Rubin’s book focuses on how to form habits based on your personality tendency. She identifies four “tendencies” (Upholders, Questioners, Obligers, Rebels) that describe how different people respond to expectations, and she tailors habit strategies to each.

-

Good Habits, Bad Habits by Wendy Wood (2019) – Written by a psychology professor who is one of the leading researchers on habits, this book gives a science-based yet accessible overview of how habits work in the brain and in our daily lives.

-

Mindset by Carol Dweck (2006) – While not about habits per se, this classic book on growth mindset vs. fixed mindset is a great companion because Atomic Habits heavily implies a growth mindset (the belief that you can improve through effort). Dweck’s research shows that adopting a growth mindset leads to persistence and embracing challenges – qualities that will supercharge your habit-building journey.

-

Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength by Roy Baumeister and John Tierney (2011) – This book explores the science of self-control and willpower. Interestingly, Clear suggests designing habits to minimize reliance on willpower, but it can still be illuminating to understand willpower’s role and limits.

-

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein (2008) – This is more about public policy and decision-making, but it dovetails with Atomic Habits on the concept of choice architecture (designing environments to influence behavior). Thaler and Sunstein discuss how small changes in how choices are presented (nudges) can lead people to better decisions without removing freedom of choice.

-

Research articles on habit formation and behavior change: If you want to go straight to the scientific source, consider reading Phillippa Lally’s 2009 study on habit formation (published in the European Journal of Social Psychology), which famously found it takes on average 66 days to form a habit (with wide variation).